About the University of Leicester

Mike Le Bas

We are saddened to learn of the passing of Dr Michael John Le Bas, who was Senior Lecturer in Igneous Petrology in the Department of Geology from 1961 to 1992.

We are saddened to learn of the passing of Dr Michael John Le Bas, who was Senior Lecturer in Igneous Petrology in the Department of Geology from 1961 to 1992.

Born in Valenciennes, France on 31 May 1931, Mike Le Bas graduated from University College, London in 1952 with a BSc in Geology with Chemistry and Mathematics and gained his PhD at Cambridge four years later. After a period of military service that included operating landing craft during the Suez campaign, he entered an academic career that included the Universities of Cambridge, Oxford, Leicester, Southampton, Queens Belfast and the Open University.

He was Vice President of the Geological Society of London 1985-1986 and served three terms as Chairman of the Geology Section of the Leicester Lit&Phil. He was a Life Member of the Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and a Senior Fellow of the American Mineralogical Society. Dr Le Bas passed away on 24 December 2022 at his home in Blandford Forum, Dorset at the age of 91.

Aftab Khan, Emeritus Professor of Geophysics, writes:

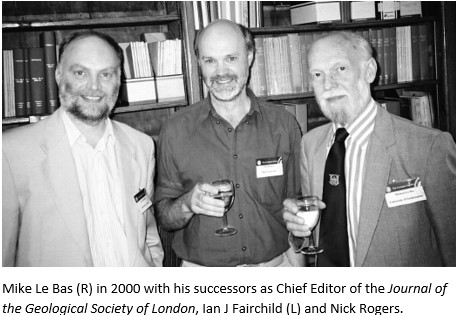

Mike Le Bas was an astute field geologist and superb petrologist. He made notable contributions to many fields including the study of ring complexes, alkaline magmatic provinces, igneous geochemical data bases, and the classification and nomenclature of igneous rocks. He served the community with distinction as the Managing Editor of the Journal of Petrology for six years and the Journal of the Geological Society of London for 13 years; and as the national representative on international committees. His encyclopaedic knowledge of igneous petrology made him a popular lecturer, examiner and referee for international journals. He supervised 23 PhD students, many of whom went on to great things in their own right.

In 1961 he was the first lecturer to be appointed by Peter Sylvester-Bradley, the first Bennett Professor of Geology. The University of Leicester was expanding rapidly after it gained University status in 1957 and it was keen to develop its science faculty. The expectations for geology were high, despite the fact there were already over 30 well established departments in the country producing 20 times as many geologists as the country needed. It was the subject of an editorial in Nature, the most prestigious scientific journal in the world.

However, being the youngest department in the country turned out to be a great advantage as the subject was undergoing a revolution in our understanding of how the Earth works through studies in magnetism, seismology, radiometric dating and observations at sea. The resulting Plate Tectonic hypothesis also changed our models in the exploration for resources mankind needed for survival and in the study of hazards. The new staff, including Mike Le Bas, were educated in these new ideas. New undergraduate and postgraduate courses emerged and by the time the first national review of earth sciences was carried out in 1989, three departments in the UK were rated as being outstanding: Cambridge, Leeds and Leicester.

Mike’s role in the development of the Department was crucial. He provided the leadership in a major part of the subject and interacted with other disciplines as computers were beginning to be used in the subject for data management and modelling. He arrived as a young man with a high reputation based on his PhD work on the Carlingford ring complex in Northern Ireland. His supervisors at Cambridge were Cecil Tilley and Stephen Nockolds. The external examiner was James Richey, the world authority on igneous ring complexes. All three were Fellows of the Royal Society and were unanimous in their praise for Mike in his interpretation of the complex based on field and geochemical data.

After national service, Mike returned to his former department in Cambridge as a demonstrator before being appointed at Leicester in 1961. He immediately took an interest and advanced our knowledge of the local geology which would be used to introduce students to field geology. He contributed a chapter in the book edited by Peter Sylvester-Bradley and Trevor Ford, The Geology of the East Midlands, which was the background reading for some courses. He later wrote an important paper on the Caledonian igneous rocks beneath eastern and central England.

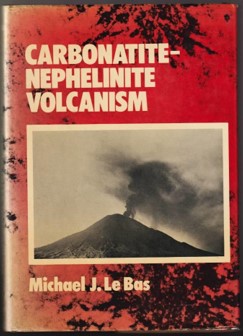

A major career development occurred when he teamed up with Professor Basil King of Bedford College and was joined at Leicester by Diana Sutherland on a NERC-funded project to investigate the alkaline volcanics and carbonatites in western Kenya. This led to Mike’s book Carbonatite-Nephelinite Volcanism which became the landmark publication on these exotic rocks. He continued to work on carbonatites in Africa, Pakistan, Russia and elsewhere – which led to current models of carbonatite genesis.

The East African Geological Research Group’s work extended to the volcanicity and tectonics of the classical rift in Kenya, which was first described by Gregory at the end of the 18th Century and attracted the attention of geologists everywhere. Its significance only became apparent with the emergence of the Plate Tectonic hypothesis in the mid-1960s. It appears to be the only place on Earth where we are witnessing a continent in the act of breaking up. Arabia has already broken off and the East African Rift system appears to be an incipient plate boundary. By the 1980s rifts were discovered on other planets and planetary scientists became interested in East Africa which became the subject of a 20-year international seismic project, KRISP (Kenya Rift International Seismic Project), co-ordinated by Leicester with the USA and Germany as equal partners. Its publications were the most cited in its day. It is one of the hundred items highlighted in the University centenary book. Leicester’s role in this would not have developed without Mike’s enthusiasm.

The East African Geological Research Group’s work extended to the volcanicity and tectonics of the classical rift in Kenya, which was first described by Gregory at the end of the 18th Century and attracted the attention of geologists everywhere. Its significance only became apparent with the emergence of the Plate Tectonic hypothesis in the mid-1960s. It appears to be the only place on Earth where we are witnessing a continent in the act of breaking up. Arabia has already broken off and the East African Rift system appears to be an incipient plate boundary. By the 1980s rifts were discovered on other planets and planetary scientists became interested in East Africa which became the subject of a 20-year international seismic project, KRISP (Kenya Rift International Seismic Project), co-ordinated by Leicester with the USA and Germany as equal partners. Its publications were the most cited in its day. It is one of the hundred items highlighted in the University centenary book. Leicester’s role in this would not have developed without Mike’s enthusiasm.

Remarkably, despite a full teaching load including field work and a busy programme of research with 23 PhD students at Leicester, and collaborators in the British Museum and elsewhere, Mike was the highly successful managing editor for 13 years of the Journal of the Geological Society of London. It is one of the oldest and most influential geological societies in the world and covers all aspects of Earth sciences. For these achievements and services to the community, Mike was awarded the prestigious Major Edward Coke Medal of the Geological Society in 1997.

Mike retired formally in 1992 after 31 years of outstanding service to the University and the geological community. But he continued his research and editorial interests as an Honorary Research Fellow in the University and as a Research Fellow of the Natural History Museum. He and his wife Pam retired to Blandford Forum. He then became a Fellow at the University of Southampton where his son Tim is a geophysicist in the Institute of Oceanography.

Mike was not in retirement mode in Blandford. He seized the opportunity to make a notable contribution as the curator of the town museum. He built displays and collections of the famous local rocks, organised public lectures and led field trips. His impact on the region was considerable. He was made a Freeman of the City in 2019. It was an award which delighted him at the end of a long and distinguished scientific career. Pam predeceased him in 2010. At Leicester they had many friends in the University and the city as Pam was also a school teacher. They are survived by three sons, all of whom have careers in education, and by several grandchildren.