Celebrating 100 years

Research

Finding a King in a Leicester car park may be one of the most headline-grabbing stories of our research, but it is by no means the beginning and end of the story of our research.

From the first PhDs we issued to discovering DNA fingerprinting to solve crimes our researchers have always looked to use their research rigour to change the world for the better.

Our first doctorate

First PhD shows commitment to original research from the outset

The first doctorate awarded at Leicester was in 1924 to founding Geography Lecturer, Patrick Bryan, who earned a University of London PhD for ‘An enquiry into the major geographical factors conditioning the production and distribution of coal and iron in the United States of America,’ (shown being congratulated by our first Principal, Robert Rattray).

The first doctorate awarded at Leicester was in 1924 to founding Geography Lecturer, Patrick Bryan, who earned a University of London PhD for ‘An enquiry into the major geographical factors conditioning the production and distribution of coal and iron in the United States of America,’ (shown being congratulated by our first Principal, Robert Rattray).

“It shows the importance of original research to the University right from its earliest years,” says William Farrell, Research Services Consultant for the Library.

Bryan drew on his thesis for his book North America: An Historical, Economic and Regional Geography, co-authored with LL Rodwell Jones, which became a standard text in print for 40 years. His Man’s Adaptation of Nature: Studies in Cultural Landscape was ahead of its time. A negative review of some of his work unfairly affected his research career, and Bryan was overlooked for a Chair when these were introduced. He was, however, awarded a long-overdue Honorary Professorship in his final year of work.

Bryan remained at Leicester for over 30 dedicated years. He served as Acting Principal before Frederick Attenborough’s arrival, he was Director of Vaughan College during the Second World War, a Vice-Principal for 15 years and Dean of the Faculty of Arts from 1942.

Discovery of King Richard III

When King Richard III was found, history was rewritten

Sometimes it still seems like a dream.

Sometimes it still seems like a dream.

In August 2012, the University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) began to dig in a Council car park to look for evidence of a friary believed to have been where King Richard III was buried in 1485 after the Battle of Bosworth.

The first trench contained a pair of leg bones and, 11 days later, an S-shaped spine was revealed. It had been accepted that Richard III’s deformity was Tudor propaganda. History was being rewritten and announced to the world.

Comparing DNA from the bones found with that from living relatives showed the remains were those of King Richard III. They were kept at the University until reburial in Leicester Cathedral in 2015.

The Herbarium

A place where thousands of plants are stored and studied

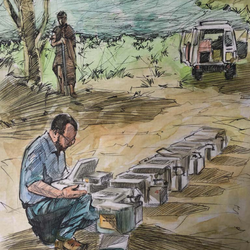

The Herbarium has over 120,000 specimens, mainly from the British Isles, Europe and the Mediterranean.

The Herbarium has over 120,000 specimens, mainly from the British Isles, Europe and the Mediterranean.

It stores voucher specimens (identified by experts as representative of their species) and has rescued plant specimens from loss. It serves many student, researcher and volunteer activities on a daily basis.

“The Herbarium’s internationally important collection informs our knowledge not only of botanical taxonomy but also diversity and genetics,” says alumna Lynda Wight.

It was set up by Thomas Tutin, Head of Botany, and Ted Horwood, Laboratory Steward, in 1945. Their research and work on the Herbarium made significant contributions to scientific and public knowledge.

The Herbarium is a much-loved collection and even retired botanists find it difficult to leave. “Professor Tutin, as an elderly gentleman, was almost always to be found studying in the corner,” recalls Wight.

Our Fellows of the Royal Society

The eminent academics who became Fellows of the Royal Society

Professor Hans Kornberg is shown here in his lab around the time he became the University’s first Fellow of the Royal Society in 1965 for his work on metabolic pathways in microorganisms.

Professor Hans Kornberg is shown here in his lab around the time he became the University’s first Fellow of the Royal Society in 1965 for his work on metabolic pathways in microorganisms.

Also achieving Fellowships were botanists and married couple Thomas Tutin and Winifred Pennington. Pennington was awarded hers in 1979 for providing the first evidence for climate change in Britain. Tutin’s was awarded in 1982.

Our Fellows include Ronald Whittam (Physiology), Ken Pounds (Physics), Martin Symons (Chemistry), Alec Jeffreys (Genetics) and Peter Sneath (Microbiology).

Leicester also proudly boasts many Fellows of the Royal Academy of Engineering, the British Academy, the Academy of Social Sciences and the Academy of Medical Sciences.

Cardiovascular Sciences

Close to all our hearts: cardiac research for better health

Studies on heart health and disease in our Department of Cardiovascular Sciences bring genuine benefits to patients.

Studies on heart health and disease in our Department of Cardiovascular Sciences bring genuine benefits to patients.

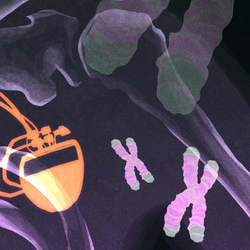

Genetic research here is looking at the inheritance and development of conditions such as coronary artery disease and high blood pressure. It is also examining the role of biological ageing in cardiovascular disease, focusing on body cell telomeres – the highlighted ends of the x-shaped chromosomes illustrated – which shorten with age.

Ground-breaking clinical research has involved pioneering use of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, robotic heart surgery, implanted pacemakers and cardioverter defibrillators (shown) and the prediction and prevention of sudden cardiac death.

We are changing the lives of patients across the world.

Our Science labs

Rapid growth of the science departments

At the beginning, the University College had 19 basic rooms, which limited what could be taught.

At the beginning, the University College had 19 basic rooms, which limited what could be taught.

In 1922, the only laboratory was for Botany; Physics and Chemistry were established after a fundraising appeal in 1924. Today, the University enjoys a global reputation for scientific teaching and research, partly thanks to its facilities.

The first purpose-built science building was the Astley Clarke Laboratories in 1951; this was followed by buildings for Chemistry, Geology, Physics and Engineering.

The Adrian Building (1966) housed the new Biological Sciences Department under Professor Hans Kornberg, shown here in the laboratories.

Later came the Maurice Shock Medical Sciences Building (1974) and the George Davies Centre (2016), followed by Space Park Leicester, scheduled to open during our centenary year.

Climate and sustainability

Tackling the climate emergency, locally and internationally

The University is active in protecting the environment. We spearheaded satellite observations of climate change and our research ranked first in the world for research in the ‘Life on Land’ UN Sustainable Development Goals category.

The University is active in protecting the environment. We spearheaded satellite observations of climate change and our research ranked first in the world for research in the ‘Life on Land’ UN Sustainable Development Goals category.

Our pioneers include Winifred Pennington FRS, who found the first evidence for Britain’s climate change, Peter Sylvester-Bradley, an early adopter of the green movement, and Paul Monks, who leads our air-quality research and became a Government Chief Scientific Adviser.

The Centre for Environmental Health and Sustainability carries out multidisciplinary research, and we are working to protect peatlands in places as far apart as the Fenlands, Indonesia and the Congo.

Locally, Research in Action addresses local social, economic or environmental sustainability issues and our campus is becoming a biodiverse haven.

The discovery of DNA fingerprinting, 1984

DNA fingerprinting catches a double murderer

Genetic fingerprinting was born at the University at 9.05am on 10 September 1984. Professor Alec Jeffreys, analysing patterns in DNA from a lab technician and her parents, found DNA ‘fingerprints’ could show relationships between people.

Genetic fingerprinting was born at the University at 9.05am on 10 September 1984. Professor Alec Jeffreys, analysing patterns in DNA from a lab technician and her parents, found DNA ‘fingerprints’ could show relationships between people.

The technique was used in an immigration case and then a paternity case. Then a double murder investigation established it in forensics.

Two teenage girls had been raped and murdered in Leicestershire, and a local man had confessed to one murder but denied the other. A detective enlisted Professor Jeffreys’ help – and the results showed the accused had committed neither. Testing other local men led to a conviction.

Professor Jeffreys was awarded a knighthood and the Royal Society’s Copley Medal. He was also made a Companion of Honour.

East African Rift geophysical research project

The heart of research on the East African Rift

Leicester Geologists have been at the centre of international study of one of the main tectonic structures on the planet for nearly 60 years.

Leicester Geologists have been at the centre of international study of one of the main tectonic structures on the planet for nearly 60 years.

Originally led by Professor Aftab Khan in the early 1960s, the project involved collaboration with European, American and African universities and other institutions through the 1980s and 1990s.

It has provided opportunities for many research students to work in Africa and brought global acclaim for the School of Geography, Geology and the Environment.

Through study of active continental rifting, where plates of the Earth’s mantle move away from each other, the work has verified a key principle of plate tectonic theory.

This work has led to more advanced studies about the Rift, including earthquake prediction research.

Diabetes research

A longstanding reputation for outstanding diabetes research and care

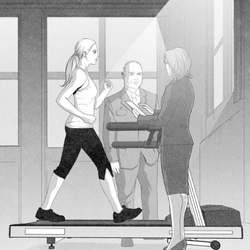

Leicester has an international reputation for excellence in diabetes research, being home to the first community diabetes clinics and the first diabetes research nurses in the UK.

Leicester has an international reputation for excellence in diabetes research, being home to the first community diabetes clinics and the first diabetes research nurses in the UK.

Professor Melanie Davies began the Diabetes Research Service in 2001 with a single Nurse Research Fellow.

Today, she and Professor Kamlesh Khunti (shown here monitoring a patient) have a team of over 160 researchers, clinicians and educationalists working on academic and commercial studies. Diabetes is relatively common in Leicester, and a lot of the work is focused on local people.

Professors Davies and Khunti lead the Leicester Diabetes Centre, which opened at Leicester General Hospital in 2012, and work closely with patients. This is one of Europe’s largest diabetes research centres.

Our 100 artwork was commissioned from Amrit Birdi and AmCo Studio Ltd and is ©AmCo Studio Ltd unless stated.

Our 100 artwork was commissioned from Amrit Birdi and AmCo Studio Ltd and is ©AmCo Studio Ltd unless stated.