Richard III: Discovery and identification

The king's grave

Although the feet and one lower leg bone (left fibula) were missing – these were removed long after burial, perhaps when a Victorian outhouse was built on top of the grave – Richard III’s skeleton was otherwise complete. It is amazing that there was so little damage, as in places, the 19th-century brickwork was just 90mm above the skeleton. If the Victorian workmen had dug much deeper or wider, Richard III’s remains might have been severely damaged or even completely destroyed.

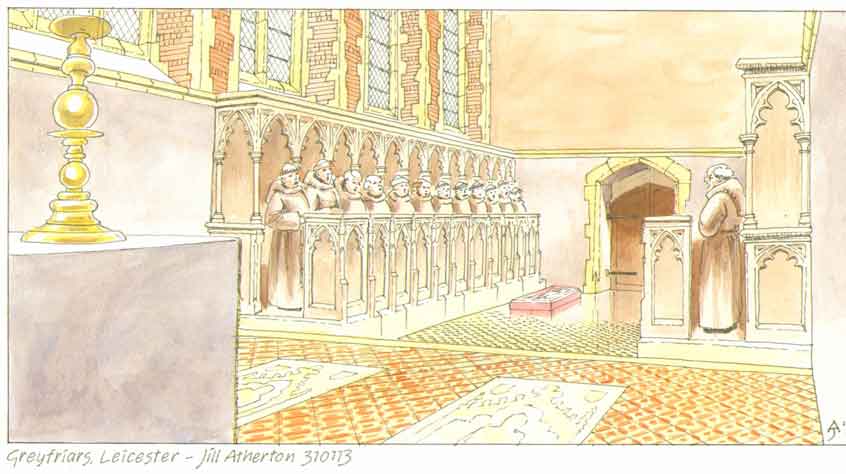

Richard III was buried at the west end of the church choir, in front of the southern choir stall. This location is slightly ambiguous. The choir was in one of the more important parts of the church, though not the most important (the presbytery), and it would have been very visible to the friars attending their daily services. However, this place was not generally accessible to the public, thereby preventing widespread veneration of the tomb. Out of sight, out of mind?

The irregular grave appeared to have been hastily dug and was noticeably too short for the body, which was propped up awkwardly at one end. Richard’s body was not in a coffin and there was no evidence that he had been wrapped in a tight cloth shroud. Instead, he lay to one side of the grave, his torso and head crammed up against the edge. This would appear to tally with historical accounts suggesting that Richard III was buried rather unceremoniously. However, it should also be remembered that he was killed in August and his corpse had been on display, unembalmed for three days before burial. Decomposition would have already started and haste may have been a necessary practicality rather than lack of respect for the deceased.

The arrangement of the body suggests it was lowered feet first, head last. This explains why the legs were straight, but the upper torso and head were partially propped against the grave side. The way the hands are arranged, crossed at the wrist (most likely right over left) and placed askew above the right side of the pelvis was unusual. It is possible that they could have been tied together, either to keep the limbs tidy or perhaps because they were never untied after Richard III was taken down from the horse which transported his corpse back to Leicester.

No traces of clothing or personal ornaments were found in the grave. This is normal in medieval burials, although kings were often buried in their official robes with emblems of office. For instance, King John (d. 1216) was buried with a sword, whilst Edward I (d. 1307) was buried with a mortuary crown and sceptre.