Richard III: Discovery and identification

The fate of the King’s body

Since Richard III’s death, many legends have arisen concerning the fate of his body. The best-known of these was published by the cartographer and antiquary John Speed in 1611. Speed wrote: ‘His [Richard III’s] body… (as tradition hath delivered) was borne out of the City, and contemptuously bestowed under the end of Bow-Bridge, which giveth passage over a branch of Soare upon the west side of the Town.’

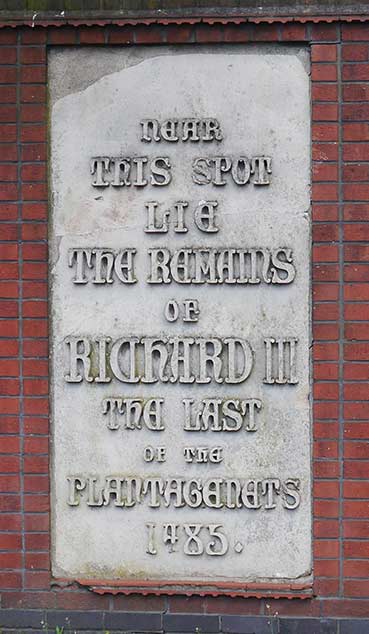

This story was first written down seventy-three years after it allegedly took place and was widely believed until the discovery of the king’s remains in 2012. It was thought that, during the destruction of the friary, Richard’s body was dug up and paraded through the streets of Leicester by a jeering mob, before finally being cast into the River Soar off Bow Bridge. The legend grew with every telling and was particularly popular in the Victorian period. In 1856 a local builder, Benjamin Broadbent, erected a memorial plaque next to the bridge, which still survives to this day.

The search for the king’s the last known resting place evolved out of a desire of Philippa Langley and others (collectively The Looking For Richard Project) to provide his story with a more credible conclusion than this popular legend.

But where did Speed get his story from in the first place? He acquired material for his book from a wide number of sources: collections of original manuscripts, some now lost; from field observations; and from works of other historians. None of Speed’s contemporaries make any reference to the purported desecration of Richard’s grave despite writing in some detail about the king’s death and burial, and his tomb. Speed may have acquired the tale from oral folk tradition but again, there are no other local sources for the story, and it may have been a tale of his own creation.

Tellingly, Robert Herrick, who owned the friary site in the early 17th century and had erected a memorial to Richard in his garden, appears to have thought otherwise. Born in Leicester in 1540, whilst the friary was still being demolished, Herrick would have had the recollections of contemporaries to help him position his monument in the correct spot. The words on the monument were unequivocal: ‘Here lies the Body of Richard III. Some Time King of England’. If anyone in early 17th-century Leicester knew where Richard III was buried, it was surely Robert Herrick not John Speed (who may never have visited Leicester), and when the king’s remains were found in 2012, they had indeed remained undisturbed for 527 years where they were originally buried.