Celebrated Rutland mosaic depicts ‘long-lost’ Troy story connecting Roman Britain to the ancient classical world

Panel 3 of the Ketton Mosaic shows Priam, king of Troy, loading a set of scales with gold vessels, to match the weight of his son, Hector. This version of the story is based on the lost play, Phrygians by Aeschylus. Jen Browning from University of Leicester Archaeological Services was able to reconstruct the burnt section by tracing the outline of the tiles. (©ULAS).

The team behind what has been described as ‘one of the most significant mosaics discovered in the UK’ have revealed that it depicts an alternative ‘long-lost’ telling of the Trojan War.

New research from the University of Leicester has conclusively determined why the famous Ketton mosaic in Rutland – one of the most remarkable Roman discoveries in Britain for a century – cannot depict scenes from Homer’s Iliad as was initially believed. Instead, it draws on an alternative version of the Trojan War story first popularised by the Greek playwright Aeschylus that has since been lost to history.

The mosaic’s images combine artistic patterns and designs that had already been circulating for hundreds of years across the ancient Mediterranean, suggesting that craftsmen in Roman Britain were more closely connected to the wider classical world than has been assumed.

The Ketton mosaic was discovered in 2020 during the COVID-19 lockdown by local resident Jim Irvine, leading to a major excavation by University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS), with funding from Historic England. The mosaic and surrounding villa complex have since been designated a Scheduled Monument in recognition of their exceptional national importance. Historic England and ULAS undertook collaborative excavations at the site in 2021 and 2022 and are working together to publish the results of those investigations.

The mosaic depicts the Greek hero Achilles and the Trojan prince Hector in three dramatic scenes – their duel, the dragging of Hector’s body, and its eventual ransom by King Priam, where Hector’s body is literally weighed for gold.

A first-century silver jug from Roman Gaul had already used same design as used in Panel 1. On the left, Achilles is sitting by his shield, surrounded by his guards. In the middle is Hector’s body in a huge set of scales, centred around a human face. At the right, king Priam in his distinctive hat and robe loads the scales with gold vessels, while his bodyguards look on. (Nineteenth-century line drawing of Berthouville Treasure, now in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France).

The Trojan War, mostly famously portrayed in Homer’s epic poem, the Iliad, was a mythological ten-year campaign by Greek forces against the city of Troy, ruled by King Priam, to reclaim the legendary beauty, Helen of Sparta.

New analysis has shown that the mosaic is not based on Homer’s Iliad, as first believed, but instead echoes a lesser-known tragedy, Phrygians, by the Athenian playwright Aeschylus. There are several retellings of the Trojan War that the Romans would have been familiar with, but the owner of the Ketton villa would have enjoyed the cachet of displaying one of the more niche versions.

The research also reveals that the mosaic’s design cleverly combines artistic patterns long used by craftspeople across the ancient Mediterranean.

|

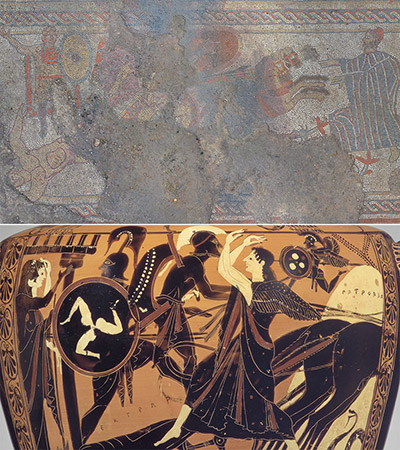

Panel 2 of the Ketton Mosaic shows Achilles dragging the body of Hector behind his chariot, while Hector’s father Priam begs him for mercy. (©ULAS). A Greek vase from ancient Athens uses the same design 800 years before the Ketton mosaic: the waving figure, shield, chariot group, running figure with arms out and even the snake curled beneath the horses all come from the same schematic. (Boston 63.473 © MFA Boston). |

Dr Jane Masséglia, lead author of this new research and Associate Professor in Ancient History at the University of Leicester, said: “In the Ketton Mosaic, not only have we got scenes telling the Aeschylus version of the story, but the top panel is actually based on a design used on a Greek pot that dates from the time of Aeschylus, 800 years before the mosaic was laid. Once I’d noticed the use of standard patterns in one panel, I found other parts of the mosaic were based on designs that we can see in much older silverware, coins and pottery, from Greece, Turkey, and Gaul.

“Romano-British craftspeople weren’t isolated from the rest of the ancient world, but were part of this wider network of trades passing their pattern catalogues down the generations. At Ketton, we’ve got Roman British craftsmanship but a Mediterranean heritage of design.”

Jim Irvine, who discovered the Ketton mosaic on his family farm in 2020, said: "Jane’s detailed research into the Rutland mosaic imagery reveals a level of cultural integration across the Roman world that we’re only just beginning to appreciate. It’s a fascinating and important development that suggests Roman Britain may have been far more cosmopolitan than we often imagine. The new paper is a suspenseful and thrilling narrative in its own right which deserves recognition."

Rachel Cubitt, Post-Excavation Coordinator at Historic England, said: “Working in collaboration with the University of Leicester brings an added dimension to investigations at the Ketton villa site. This fascinating new research offers a more nuanced picture of the interests and influences of those who may have lived there, and of people living across Roman Britain at this time.”

Hella Eckhardt, Professor of Roman Archaeology at the University of Reading, who was not involved in the study, said: “This is an exciting piece of research, untangling the ways in which the stories of the Greek heroes Achilles and Hector were transmitted not just through texts but through a repertoire of images created by artists working in all sorts of materials, from pottery and silverware to paintings and mosaics.”

- Troy Story: The Ketton Mosaic, Aeschylus, and Greek Mythography in Late Roman Britain, by Jane Masséglia, Jennifer Browning, John Thomas and Jeremy Taylor, is published online in the journal Britannia 2025, DOI: 10.1017/S0068113X25100342

Section of Panel 1 of the Ketton Mosaic shows Hector, prince of Troy, in his chariot. (©ULAS). A second-century Roman coin from Ilium in Turkey, labelled ‘Hector’, is an earlier example of the same design. (RPC 4.2.120 @ RPC online).