Jupiter's crowning glory

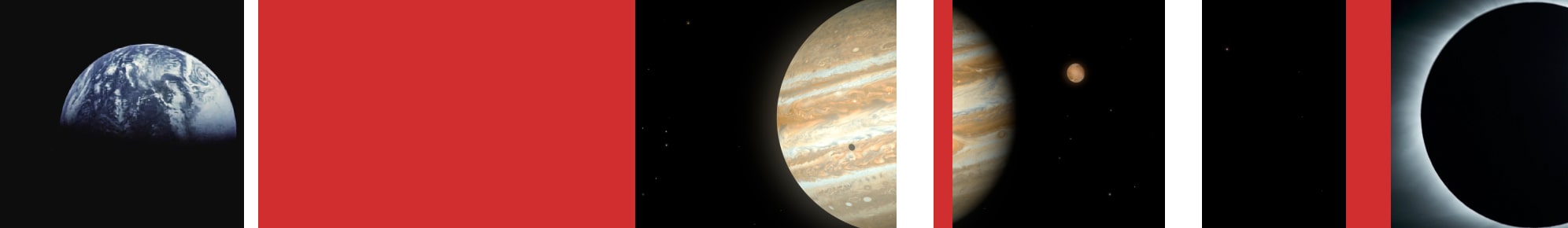

On 5 July 2016, four years and 11 months after launching from Cape Canaveral, NASA’s Juno spacecraft entered a polar orbit around Jupiter. It was a full 13 years since Professor Stan Cowley from our Department of Physics and Astronomy became attached to the project as Co-Investigator. Interplanetary missions work on long time-scales.

Unlike some other missions, there is no actual University of Leicester manufactured hardware aboard Juno – but a great deal of University of Leicester expertise is evident both in the development of the mission and the analysis of its results. The University was involved with Cassini’s visit to Saturn and that experience, in tandem with more than half a century of space research, made Leicester an obvious choice for the UK element of Juno.

The spacecraft’s initial orbit took 53.5 days to complete; the plan was that on the third orbit Juno would move closer into a tight 14-day orbit. However, something curious happened with the software – an unexpected reboot – and until the NASA team can determine why that happened, Juno is staying in the larger orbit.

The important thing to remember is the spacecraft is most definitely still working. The Juno team are right to be cautious about performing the engine burn, there’s no point in taking unnecessary risks, especially when Juno can still take measurements in the 53.5 day orbit. By staying in this longer orbit for an extended period of time, Juno will be further away from Jupiter, therefore spending less time in the extreme radiation environment of Jupiter’s magnetic field.

“The important thing to remember is the spacecraft is most definitely still working,” emphasises Rosie Johnson on the University’s Leicester to Jupiter blog. “The Juno team are right to be cautious about performing the engine burn, there’s no point in taking unnecessary risks, especially when Juno can still take measurements in the 53.5 day orbit. By staying in this longer orbit for an extended period of time, Juno will be further away from Jupiter, therefore spending less time in the extreme radiation environment of Jupiter’s magnetic field. This will actually extend the life-time of the mission since the instruments will spend less time being exposed to the harsh radiation. The mission can still achieve all of its scientific goals, but we just have to be more patient before we get the final answers.”

While much of Juno’s scientific work was delayed, Rosie – along with Dr Jonathan Nichols and Dr Tom Stallard – was able to conduct some impressive Jupiter research from a distance using Earth-based and space-based facilities including the Hubble Space Telescope. Their interest lies in the planet’s auroras, visually stunning displays of light caused by electrically charged particles racing down Jupiter’s magnetic field lines into the polar region, the Jovian equivalents of our own Northern and Southern Lights.