Tackling sexual violence

In low-resource environments, such as developing countries, displaced communities, and humanitarian crises, sexual violence is a common occurrence but very few cases are reported or prosecuted. In many cases, a lack of access to physical evidence is allowing the guilty to walk free. Professor of Criminology Lisa Smith’s research in forensic science and criminology is breaking this cycle of impunity.

To tackle the issue of collecting DNA evidence, Professor Smith joined forces with fellow University of Leicester academics Mark Jobling, Professor of Genetics, and Dr Jon Wetton, expert in genetic profiling. The interdisciplinary Leicester team works closely with Kenyan activist Wangu Kanja, herself a victim of sexual violence, as well as the Nairobi Women’s Hospital Gender Violence Recovery Centres, and collaborators at Kenyatta University, who have visited Leicester and collaborated in research to understand genetic diversity in Kenya.

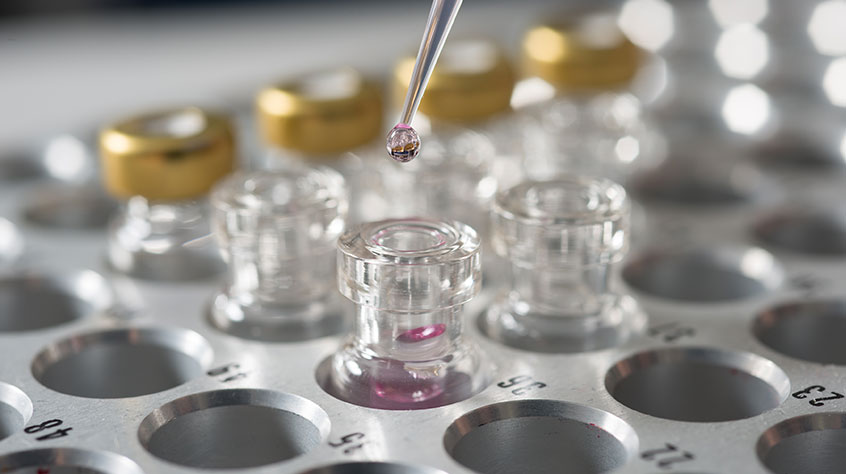

The Leicester-Kenya team has developed a new low-cost, easy-to-use DNA kit that is currently being used in healthcare clinics across Kenya.

We have heard some harrowing stories from survivors of sexual violence. Right now there is a sense of helplessness and a lack of confidence in the criminal justice process. This kit provides some hope for access to justice for victims.

Funding provided by the Ring for Peace Foundation has enabled training of over 500 healthcare workers, volunteers, and police staff and the distribution of 1200 DNA kits to Nairobi Women’s Hospital Gender Violence Recovery Centres. Nearly 200 DNA kits were used with survivors between December 2020 and April 2021.

Lisa said: “The key is to build trust in the response to sexual violence and allow survivors to take ownership of the recovery of DNA.”

The CSI effect

The hope is that this simple kit will give the criminal justice system in these areas the scientific evidence it has so far lacked, encouraging victims of sexual violence to come forward and support prosecutions.

Professor Smith said: “Time is of the essence for DNA. If you don’t take samples within 72 hours you are very unlikely to recover any DNA. So, rather than saying because of where you are there is no potential for DNA recovery, this is something that can be used as an alternative.

“A lot of cases aren’t coming to court because there is no DNA. The whole point of this kit is that it can be made available in the field where proper medical examinations can’t be carried out.”

For Lisa the problem was brought into sharp focus when she attended the 2014 Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict.

She said: “The summit got me and the team thinking about how we might work with partners in Kenya to co-develop innovations that would help tackle sexual violence and bring perpetrators to justice in places where there are very few opportunities to have forensic science play a role in prosecutions.”

A project of passion

This research is now the main focus of Lisa Smith’s academic work. Since 2015, the team has received funding from the Global Challenges Research Fund, Humanitarian Innovation Fund, and the Ring for Peace Foundation to support this work. In 2018, the research project won the 2018 Times Higher Education award for Research Project of the Year: Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences.

The Leicester-Kenya team has taken tried and tested DNA technology and adapted it to work in a new context.

Mark Jobling, an expert in forensic genetics, said: “Back in the 1980s Alec Jeffreys pioneered genetic technology for individual identification, and here we’re embedding state-of-the-art DNA profiling as part of our Kenyan project”.

The pilot kits were manufactured by their industrial partner Scenesafe, specialists in evidence recovery systems.

Lisa said: “These kits will give the police and prosecutors robust evidence to put before judges and juries to get a conviction. It will be especially important in cases where the victim can’t identify the perpetrator.”

The DNA kits are currently being used in healthcare clinics across Kenya, providing improved methods for collection, preserving, and protecting DNA evidence.

Giving hope to victims

In Kenya - and beyond - the aim is for the DNA kits to make it possible to recover evidence even where accessing medical examinations is difficult or impossible. But the situation is even more complex than that and there are many cultural and legal challenges to overcome.

“In some places the first step is raising awareness that sexual assault is a crime and when it happens something needs to be done about it. Where legislation does exist, how do you support survivors and investigate these crimes effectively? How do you encourage people to report sexual violence? Can you prosecute it successfully? And how are perpetrators held accountable?”

“In many places prosecutions never happen so victims are very unlikely to report sexual violence because it is putting them through a lot of secondary trauma and they know there’s not going to be justice at the end of the process. It means there is a complete lack of hope.”

Someone who knows this from personal experience is Wangu Kanja who has established the Wangu Kanja Foundation. Wangu was raped during a car-jacking incident in 2002. The offender was never identified. She is now a fierce advocate for reform and justice for survivors in Kenya.

Grass roots partnerships are vital

The difficulty is reaching people living in complex environments where rape and sexual violence are commonplace. People like Wangu can make this possible.

Lisa said: “There are incredible organisations working around the world, grass roots community groups, who realise the scale of the problem because they are living it and are really committed to working with their communities to raise awareness that sexual violence is not right and it is a crime. Their work is absolutely vital to achieving impact on the ground.

“You can have the best idea in the world but you need to make sure you are answering questions that stakeholders are actually asking and that what you are doing is culturally relevant and impactful.”

Wangu adds: “It is vital for us as a country to ensure that we can use DNA evidence in cases of sexual violence, as a means to support survivors in accessing justice.”

The questions they hope to answer

Police have already started collecting the DNA kits from healthcare clinics to assist with their investigations, so the next big milestone will be when the evidence is used in the courts. Longer term, the team are interested to see how it impacts on the reporting of sexual violence and deterring offenders. They also want to know how it might transform the criminal justice system in these areas.

“The next big moment will be the first time the DNA kit goes to court. That will be a crucial turning point. In Kenya they already accept DNA as evidence in court and we are very much looking forward to the first success with these DNA kits,” comments Lisa.

Thinking big

The team would like to see this DNA kit made available in all kinds of low resource situations. They would also like to see an agency such as the UN using them when they are deployed to humanitarian and disaster areas. And as a result of the Oxfam scandal they are also talking to organisations tackling sexual violence in the Aid sector.

“If we can demonstrate the principle and the integration of it in a setting like Kenya then hopefully agencies will pick it up and deploy it in more complex places."