Fight against tuberculosis

Tackling TB: the world’s most deadly infection

Every year millions of people across the world fall ill with tuberculosis (TB), a bacterial infection that gains access through the lungs. The disease is partially preventable through vaccination and treatable with antibiotics, yet each year it affects up to 6,000 people in the UK and more than 10 million people worldwide. With 1.5 million TB deaths recorded annually it is the largest infectious cause of death globally.

Although TB is found all over the world, the majority of people who contract it live in low- or middle- income countries; with approximately half of all patients found in Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines and South Africa. The disease is the leading cause of death of people with HIV, and as it requires lengthy treatments with antibiotics it often associated with antimicrobial resistance.

Leading the fight

Mike Barer, Professor of Clinical Microbiology and Honorary Consultant Microbiologist at the University of Leicester’s Department of Respiratory Sciences, works at the interface between bacterial physiology and human infection, focussing on tuberculosis and on microbiome studies.

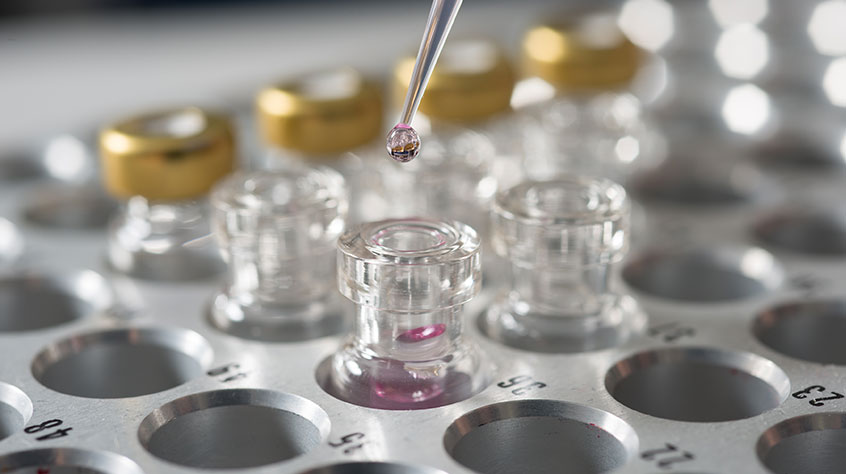

Professor Barer is revolutionising understanding and diagnosis of TB. Working in collaboration with academics from the University of Pretoria in an MRC-GCRF funded project, he has developed a way of detecting TB bacteria breathed out into face masks. With Professor Jingzhe Pan in our School of Engineerring, he has developed a 3D printed strip which is inserted into masks to take the samples. The approach has clear potential to change the way we detect infectious TB and save millions of lives across the world.

Designed and printed at the University, the insert captures and stabilises TB bacteria breathed out by infected individuals in masks worn for just thirty minutes. A lab test taking less than two hours is then used to detect the bacteria. Promising early results show that mask sampling can detect the infection several weeks before established methods such as chest x-ray and phlegm sample analyses. Mask sampling detects patients who are infectious at an early stage and stops them spreading infection as early as possible, something other tests may miss for several weeks.

Unlike a blood test, which cannot differentiate between active and dormant TB, the mask provides rapid detection of bacteria, offering a more direct indicator of how infectious individuals are compared to traditional sputum samples, reducing the need for invasive investigation.

It costs the NHS £1.8m annually to test for TB in adults – in comparison, the mask and insert materials cost around £2 and once in industrial production could cost just pennies per mask, potentially making valuable savings for health services around the world.

This is the first time that exhalation from prospective patients with TB can be captured in such a quick and simple way. This pioneering research provides the opportunity to save thousands of lives every year across the world by early detection of a treatable disease – it is world-changing.

“The fact that the mask is a low cost and appears to detect TB bacteria before they appear in sputum has major implications for early detection of disease and access to treatment. We are really excited about taking this forward to influence the spread of airborne infection. The mask insert approach has the potential to save millions of lives globally, being easily accessible and cost effective to produce.”

Adapting to the coronavirus crisis

Building on the early success of the Face Mask Sampling system in detecting TB, Professor Barer has adapted the mask approach to detect COVID-19 virus particles.

This approach to testing for coronavirus could determine whether a person is infectious or not – even before symptoms are present. If successful, the approach could greatly simplify large scale screening for the virus and curb the spread of the disease. Using the adapted mask to screen for coronavirus could allow very large groups to be checked at once, potentially helping to curb the spread of the virus and avoiding long stays in quarantine.

Prevention is better than cure

Professor Barer is working on a further project with the University of Pretoria to increase health literacy throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Smart-phone compatible videos are being developed to disseminate culturally targeted information to vulnerable populations in Pretoria via mobile phone networks.

The risk of contracting COVID-19 is increased by the spread of misleading information, so this project has been designed to encourage the behaviours that could help limit the epidemic and sustain pre-existing healthcare needs. Drawing on the University of Pretoria's clinical and healthcare expertise, the team are creating a series of short animated videos to help the public understand the critical role they play in preventing and containing the spread of COVID-19. The series of 20 visually compelling and culturally targeted videos will be published in five main South African languages with scope to add additional local languages.

This project is part of the University of Leicester’s portfolio of Global Challenges Research Fund projects, carrying out cutting-edge research in partnership with local universities, policymakers and communities that addresses the challenges faced by countries experiencing chronic disadvantage. The University of Leicester was one of only ten institutions across the country commended by Research England for its GCRF strategy.