History at Leicester

Cricket Country

Professor Prashant Kidambi discusses his latest book, Cricket Country: An Indian Odyssey in the Age of Empire (Oxford, 2019).

'Cricket is an Indian game accidentally discovered by the English,' it has famously been said. Today, the Indian cricket team is a powerful national symbol, a unifying force in a country riven by conflicts. But India was represented by a cricket team long before it became an independent nation.

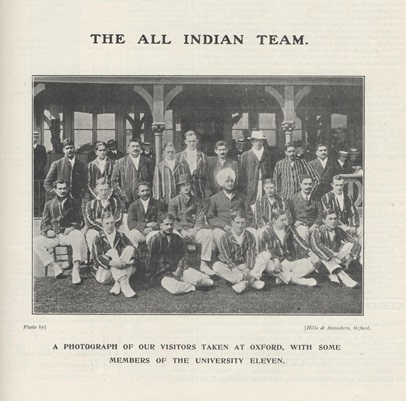

Drawing on a diverse range of original archival sources, Cricket Country tells the astonishing story of the first ‘All India’ cricket team. Conceived by an unlikely coalition of imperial and local elites, it took twelve years and three failed attempts before this Indian cricket team made its debut on the playing fields of imperial Britain in the blazing coronation summer of 1911.

I have long had an interest in the social and political history of sport. And as an historian of modern India, I have been particularly fascinated by the history of cricket. From the outset, cricket has mirrored both the sectionalism and solidarities of a deeply divided and unequal society. Recovering and recounting the long-forgotten story of the first All India cricket team gave me the chance to explore the history of an extraordinary event as well as its relevance for contemporary Indian society.

This is a tale with an improbable cast of characters set against the backdrop of anti-colonial protest and revolutionary politics. The team’s captain was the Maharaja of Patiala, the young, embattled, ruler of the most powerful Sikh state in colonial India. The other team members were chosen on the basis of their religious identity. Remarkably, two of the cricketers were Dalits, who faced horrendous forms of caste discrimination. Over the course of a historic tour of Great Britain and Ireland, these Indian cricketers participated in a collective enterprise that highlights the role of sport in fashioning the imagined communities of empire and nation.

The project began life as a specially commissioned essay for the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, to mark the centenary of the 1911 All India cricket tour of Great Britain and Ireland. But it quickly became apparent that this astonishing story needed a larger historical canvas. Happily, the Leverhulme Trust awarded me a Research Fellowship, which allowed me to pursue the project.

Fortunately, too, this is a period for which we have rich source materials, much of it available in archives in India and the UK: official records, newspapers (both in English and Indian regional languages), memoirs, diaries, and private papers. Finding this material was challenging at times, as was the writing. For no story is simply given; the historian actively shapes the material. Inevitably, making choices about what to include and what to leave out was an important, and agonising, part of the writing process.

When I began the research, very little was known about this Indian cricket team and its pioneering tour of Britain. It was widely regarded as belonging to the fuzzy pre-history of Indian cricket. Nor did I have any idea at the outset that the 1911 tour was the culmination of a 12-year quest to form a composite Indian cricket team. Indeed, it was a project that galvanised large sections of the cricket-following public in the subcontinent. I also did not fully appreciate at the outset the role of the Parsi community of Bombay in this history. The stories of the individual team members—drawn from different religious communities and from all parts of India—were equally revelatory. I was particularly taken with the story of the Palwankar brothers—Baloo and Shivram—who overcame entrenched forms of caste discrimination to become the most well-known cricketers of the day. But there were other fascinating characters too: Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala, Prince Ranjisinhji, and the Muslim cricketers of Aligarh. Nor were the individual stories the only source of surprise; the summer of 1911 itself turned out to an important element in the story of the Indian cricketers’ tour. It was one of the hottest British summers on record, marked simultaneously by decorous imperial pageantry and dramatic popular protest.

At the outset, my focus was largely on the making of the first Indian team and the organization of their tour of Britain in 1911. But as I began to dig deeper, my focus widened. It became increasingly clear to me that there was a real opportunity to use this unique sporting event to reconstruct a fascinating epoch in the Indo-British relationship. The final product is thus a work of history that uses sport to explore themes that go beyond the confines of sport. My book shows how the project to put together the first Indian cricket team was shaped by race, religion, caste, class, money, and power. As the great C.L.R. James asked: what do they know of cricket who only cricket know?

Cricket Country received a generous reception from academic and non-academic reviewers. It became the first book on sport to be shortlisted for the Wolfson History Prize (2020), the most prestigious prize in History publishing in the UK. The jury described the book as ‘a superbly executed social history which defies the usual boundaries of the history of sport genre to tell a story of empire and identity’. Cricket Country was awarded the Lord Aberdare Literary Prize (the official book prize of the British Society for Sports History) and the Sports Book of the Year at the Ekamra Sports Literature Festival (Delhi, 2019). It was also shortlisted for the MCC-Cricket Society Book Award and the Derek Hodgson Cricket Book Award.

Writing Cricket Country also allowed me to engage with diverse publics, both in India and the UK. During the long gestation of the book, I used academic seminars and public talks to develop my arguments. After publication, I gave a series of talks locally, nationally and internationally highlighting its principal themes. In turn, these events created new opportunities for meaningful public engagement. In 2021, the

Marylebone Cricket Club (Lord’s Cricket Ground) invited me to act as a consultant for an internal review of its archival and museum collections aimed at identifying the broad connections between cricket, race, and empire. Subsequently, I accepted an invitation from the club to co-curate its next major public exhibition (to be held in London from May 2023). Drawing on my research, the proposed exhibition will present a more diverse and inclusive history of the ‘empire of cricket’.