Tracking alien invaders

Humanity’s influence on the planet is all around us, but some of the effects of that influence are less obvious. Yet they have huge implications for the future of the planet, and everyone and everything on it. We are at the forefront of research into how the world is changing and what we can do to steer or mitigate that change.

One of the most profound humanity-driven global changes is the spread of non-native animals and plants, which can provide an important index of how the biosphere is changing around us. Mark Williams, Professor of Palaeobiology in our School of Geography, Geology and the Environment is leading research in this area, supervising a team that includes PhD students Stephen Himson and Rachael Holmes.

The Amur River clam is just one of a multitude of species that have completely rewritten the biological make-up of San Francisco Bay. These non-native organisms are so abundant in the Bay that the biological record forming at the present day is completely unique with respect to the biological record that we can observe up until 1853, when the first non-native organism was recorded.

Biological invaders in the Bay

Stephen’s work concentrates on San Francisco Bay in the United States, which is not only one of the most biologically invaded places on Earth – with non-native species sometimes making up 97% of the life in the Bay – but also one of the best documented locations in terms of its reconfigured ecosystem. Over the past 150 years or so, more than 200 invasive species have taken up residence in the Bay, completely and irrevocably changing the existing ecology.

Many of the new species have arrived in ships’ ballast carried across the Pacific. One of the most prevalent new arrivals is the Amur River clam which is native to East Asia: Japan, Korea and particularly the area of the river on the Sino-Russian border after which it is named. Growing up to 25mm across, the clam proliferates rapidly and it is estimated that in parts of the Bay there are now over 10,000 Amur River clams per square metre.

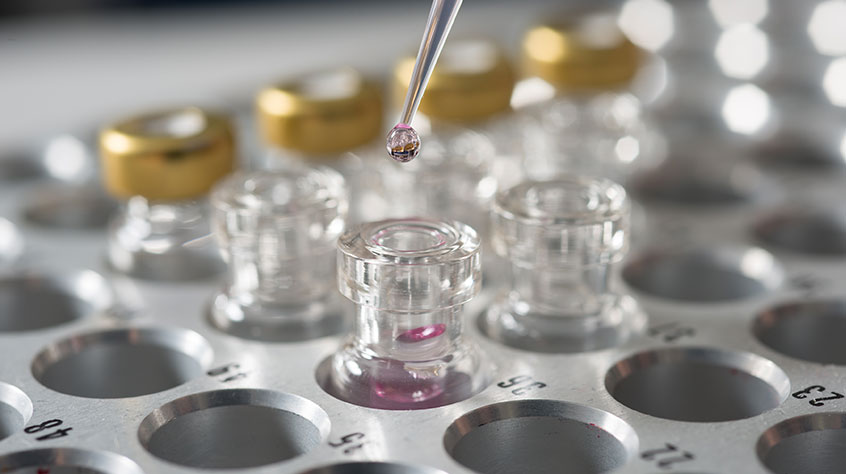

Stephen’s work has involved taking samples from the Bay’s muddy floor which reveal both the extent and the chronology of this alien invasion.

“My research is aiming to pinpoint the year in which the biological record in San Francisco Bay becomes fundamentally and unequivocally dominated by non-native species. This will serve as an example of how humans are now a geological force, with the ability to overwrite natural patterns of species distribution and cause a major shift in the biological record, hundreds – if not thousands – of times quicker than any comparable biological shift in the past.”

Homogenised continents

On the other side of an increasingly fragile looking planet, Rachael Holmes is investigating the natural world of Indonesia and how this has been impacted by humans. Key to her research is the biogeographical region of Wallacea that acts as a transition zone between the flora and fauna of Asia and those of New Guinea and Australia.

The Wallacean region was named in 1928 after the great naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, who lived in Leicester and is remembered with a plaque outside New Walk Museum. Understanding how human driven distributions of non-native species may be making Wallacea and surrounding biogeographical regions more homogenised is socially, environmentally and economically important.

Such movement is nothing new: humans have been transporting animals and plants – deliberately and accidentally – within Island Southeast Asia for at least 20,000 years. But the rate and extent of such movement has increased exponentially, especially since the globalisation of trade.

The rise of palm oil forestry

One of the most extreme examples of ecosystem reconfiguration is the African oil palm. Originally native to west Africa, this was introduced into the Indonesian archipelago in the late 19th century when palm oil became an important crop, providing a lubricant for machinery.

Since then, of course, palm oil forestry has spread on an industrial scale causing enormous changes to the local ecosystems. These changes affect an area that is styled as having ‘mega-high biodiversity’. Amongst the many species that are suffering are our close cousins, the orangutans, but they are just the tip of an ecological iceberg which Rachael’s research is highlighting.

“Non-native species provide both a cost and a benefit to the Indonesian economy as they make up the majority of cultivated crops but also the majority of agricultural weeds and invasive species,” says Rachael. “Many of the 35,000 native plants in Indonesia are endemic to the archipelago and are therefore at higher risk from introduced species that may be better adapted to human altered eco-systems.

“I am using historical records in combination with sediment samples that contain plant microfossils to better understand the relationship between human landscape change, introduction of non-native species and the response of native plant communities.”

Changing our relationship with nature

Invasive species have extended over much of the planet. Anywhere that humans go, new animals and plants accompany them and existing ecosystems are often disrupted. But while these changes are often irreversible, further change is not inevitable. Part of the research by Professor Williams’ group is into how cities - and citizens - can make a difference, effecting a change in the pattern of change.

The key, he explains, is in altering our relationship with nature from an essentially parasitic one to a mutualistic one. Instead of simply using up resources at an unsustainable rate, the potential exists to develop new ways that humans and other species can live together, combining new technology with new behaviour to provide long-term hope for the planet.

"We can think of cities as organisms. But these organisms are consuming the environment with impunity and degrading nature as a result. That is not sustainable in the long term and we need to change the way we relate to nature and live with it more harmoniously."

As with so many environmental concerns, widespread change on a micro level can have an effect on a macro level. Something simple which anyone with a garden can do is to keep part of it wild, providing a mini ecosystem for animals and plants which have been edged out of so many places by concrete and neatly trimmed lawns. And leaving a hole in the fence will allow those mini-ecosystems to join up, so that hedgehogs and other wildlife might get a better toehold.

The University is working to apply this approach to parts of our own estate – which includes not just the main campus but also the satellite Brookfield campus of the Business School as well as our Botanic Garden and the Attenborough Arboretum.

The University of Leicester may be a long way from San Francisco or Indonesia, but the principles are the same – and the potential for us all, as Citizens of Change, to make a real difference is widespread.