Uncovering the past relationships between humans and animals

Archaeologist Professor Richard Thomas researches the changing relationships between humans and animals in the past through the analysis of bones recovered from archaeological sites and explores the contemporary relevance of these findings. His research has enriched our understanding of animal health and disease, agricultural practices, human and animal diet, and the changing perception and treatment of animals. As well as journeying back through millennia, his research has extended into the Victorian era, with his ground-breaking work revealing new details about Ancient Egyptian animal mummification, analysis of some of the earliest known pets and uncovering the truth about the death of Jumbo, the world-famous elephant.

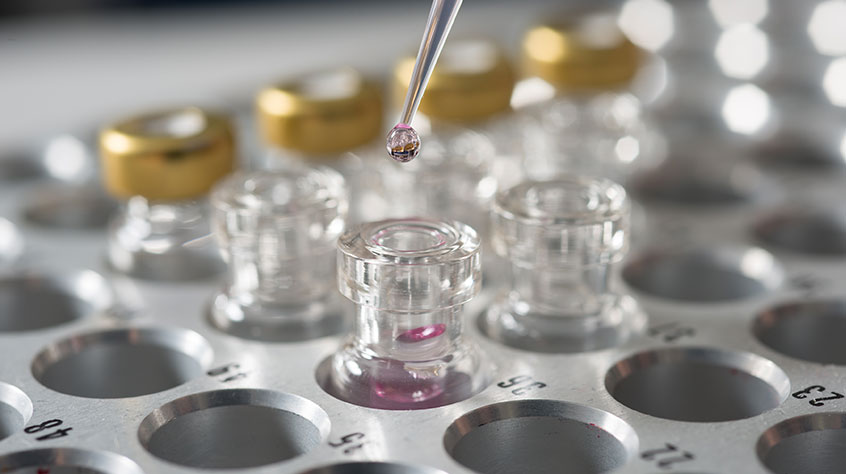

The application of new imaging technologies, alongside archaeological approaches, has the potential to transform our understanding of ancient Egyptian mummification practices, and human-animal relationships more broadly, without damaging the delicate remains.

Gifts for the gods

The central role animals held in ancient Egyptian society is widely known, but new technologies have allowed us to learn more about the ancient Egyptians’ relationship to animals through analysis of their mummified remains. Professor Thomas gained new insights into this ancient world as part of a team of researchers from the Universities of Leicester and Swansea that digitally unwrapped three mummified animals from ancient Egypt, a project covered by BBC’s Horizon in 2015.

Using X-ray micro CT scanning, which generates 3D images with a resolution 100 times greater than a medical CT scan, the remains of a snake, a bird and a cat were analysed in extraordinary detail, right down to their smallest bones and teeth, giving unprecedented insights into the animals’ lives and deaths more than 2,000 years ago.

Richard explains: “It has been estimated that there may be up to 70 million animal mummies in ancient Egypt. Many of these animals were votive offerings – animals that had been placed in temples dedicated to different gods.

“Advances in imaging technology are, for the first time, revealing new insights into the lives of these animals and mummification practices without disturbing the wrappings. In our study we were able to visualise bones and teeth, materials and even desiccated soft tissue in new levels of detail. The scans have made it possible to 3D print and handle the skeletal remains and take a virtual walk-through the mummies, revealing the impact of the industrial scale of mummification on the animals themselves.”

Animals were sometimes buried with their owner or as a food supply for the afterlife, however the most common animal mummies were offerings bought by visitors to temples to offer to the gods, to act as a means of communication with them. Animals were bred or captured by keepers and then killed and embalmed by temple priests. The findings of this study were able to identify the age of the cat due to its teeth, and found the snake had been deprived of water during its life and ultimately killed using a whipping action.

The first pet cat in Kazakhstan

Notable shifts in our relationships with animals – including the advent of keeping animals as pets - reflects wider social change. The analysis of an ancient animal skeleton uncovered in an urban settlement in Kazakhstan found the remains to be from the first pet cat found in the region, providing evidence for a fundamental change in the nature of human-animal relationships during a period of rapid urbanisation.

Professor Thomas was part of the international team that carried out a multi-disciplinary analysis on the well-preserved skeleton of the cat, which dates back to 775–940 cal CE, from Dzhankent, Kazakhstan, which is located on the famous Silk Road route. The earliest historical mention of domestic cats in this region originates from sixth century Persia, however in the steppe of Central Asia, domestic cats were not widespread until the 18th and 19th centuries.

Richard said: “The bones of animals are recovered routinely from archaeological sites. As this study shows, they have the potential to transform our understanding of the importance of animals within past societies, revealing the close connections we have had with them.

“This tom-cat lived into adulthood, was well fed and was cared for. Recovered from a city along the Silk Road, this discovery marks an important change in human-animal relations in the steppe, emphasising the important link between pet-keeping and urbanism.”

A Jumbo opportunity

Another change in the relationship between animals and humans was seen with the introduction of modern zoos and travelling circuses in the 18th century.

In 2016 Richard was approached to lead a team investigating the life and untimely death of Jumbo - the Victorian celebrity animal superstar whose story is said to have inspired the film ‘Dumbo’ - for a 2017 BBC documentary. As well as being granted unique access to Jumbo’s skeleton at the American Museum of Natural History, the project became a career highlight for Richard as he worked with childhood hero Sir David Attenborough to present his findings.

“Working alongside Sir David Attenborough has unquestionably been the highlight of my professional career. Like many, watching Sir David’s documentaries was incredibly formative during my childhood, inspiring my own love of natural history. His knowledge, passion and curiosity for all aspects of our natural world was wonderful to observe first-hand.”

After a week in New York analysing Jumbo’s skeleton, Richard’s team – which included an archaeological geochemist, geneticist and a veterinary specialist in biomechanics - built a biography of Jumbo’s life with the hope of resolving the long-standing mystery of how he died.

Jumbo’s story is both captivating and tragic. Born in Sudan in 1860 he was captured as a calf and transported to a zoo in Paris, before arriving at London Zoo in 1865 as their first African elephant. By 1882 his behaviour had become erratic and aggressive, leading to his sale to Barnum and Bailey’s travelling circus in America. There he became the centrepiece of the Greatest Show on Earth until his tragic and mysterious death in 1885. Although it was widely reported that he was struck by an unexpected freight train as he was being loaded into his boxcar, rumours circulated that he was led to his death by his keeper to prevent his failing health from coming to light. The team concluded that Jumbo was indeed struck by the train as his keeper tried to lead him to safety.

The significance of this elephant continues to be felt today. Richard explains, “Jumbo is perhaps the most famous elephant in the world. His name is now used as an adjective to describe everything from passenger planes to toilet roll.”