Richard III: Discovery and identification

Forensic analysis using micro-CT

The forensic analysis of the Greyfriars bones by micro-computer X-ray tomography (micro-CT) is the first time that this advanced technique has been applied to an archaeological investigation.

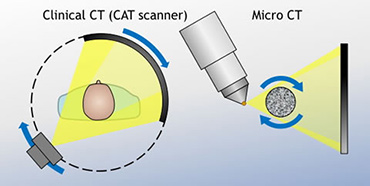

Computed X-ray tomography (CT) has routinely been used for medical applications since the early 1970s, and we are all familiar with the image of a patient sliding through a doughnut-shaped ‘CAT scanner’. An X-ray source is located on one side of the ring, an X-ray detector on the other, and the whole affair rotates around the patient. Sophisticated software is then used to turn the succession of radiographs into a 3D image.

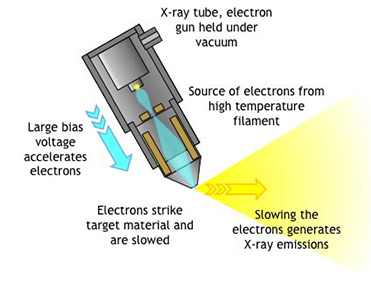

Micro-CT is a much higher-resolution technique in which the X-ray source (an electron gun in a vacuum tube, not dissimilar to the cathode ray tube in an old television) and the detector remain static while the sample rotates. The East Midlands Forensic Pathology Unit, part of the University of Leicester located on the Leicester Royal Infirmary site, and the University’s Department of Engineering are together leading in the use of micro-CT for forensic applications.

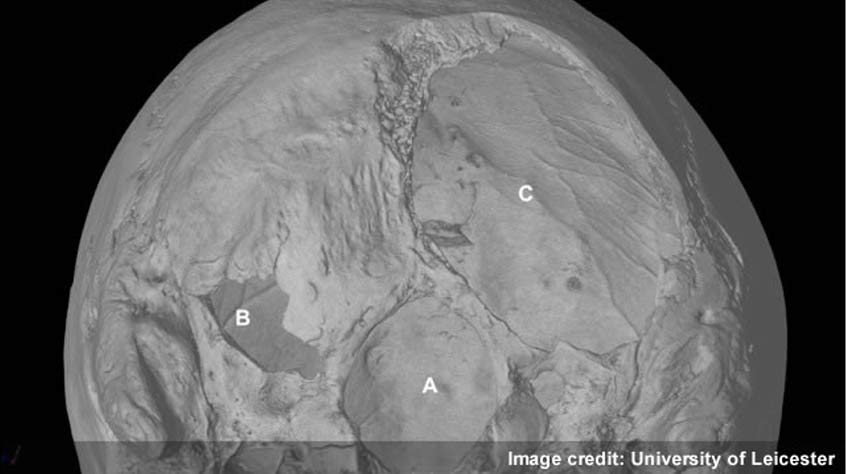

Applying the micro-CT technique to the bones found underneath the Greyfriars church allows us to study them in great detail, in particular the visible wounds and the effect of the scoliosis. The work was led by Professor Guy Rutty, Chief Forensic Pathologist and Professor Sarah Hainsworth, Professor of Materials Engineering.

Resolution

One of the most commonly asked questions about X-ray tomography is: ‘What is the resolution?’ The not terribly helpful answer is: it depends. Among other things, it depends on the size of the pixel matrix employed and the spacing of volume elements or ‘voxels’. It also depends on the resolution of the X-ray detector itself, the focal spot size, the geometric magnification, the stability of the rotation mechanism and the filtering algorithm used to reconstruct the images.

In practice, for micro-CT (and clinical CT), the geometric magnification is important, determined by how close the sample is to the X-ray emitter and the detector, always bearing in mind that the scanned object must be able to rotate through 360 degrees. Resolution is also affected by how much the object moves between each slice, with parts further away from the centre of rotation moving further.

Finally, to improve signal-to-noise ratio, long scan times may be necessary. Each bone of the Greyfriars skeleton was imaged for six to eight hours to give the highest possible resolution.