Modern Languages

Articles and features

Why this project?

by Marina Spunta, 21 November 2013

This project stems from my interest in contemporary Italian literature and photography, in the work of Gianni Celati, Luigi Ghirri and other writers and artists, and in space, place and landscape studies. My interest in Ghirri started to develop about ten years ago alongside my study of the literary representations of space and place in the work of Gianni Celati, Daniele Benati, Ermanno Cavazzoni, Giorgio Messori and other writers who collaborated to Ghirri’s projects on the Po valley in the 1980s and to Celati’s projects since then. What sparked my fascination for the work of Ghirri, Celati and others was the exhibition Racconti dal paesaggio, 1984-2004. A vent’anni da ‘Viaggio in Italia’, curated by Roberta Valtorta at the newly opened ‘Museo di Fotografia Contemporanea’ in Cinisello Balsamo (Milan), , which I saw in February 2004. Equally inspiring was listening to Gianni Celati, Gabriele Basilico, Roberta Valtorta and other artists and scholars talk about the importance of that experience at a seminar organised in occasion of the exhibition. In May 2007 I organised with Laura Rorato a conference on ‘Letteratura come fantasticazione’ at the University of Leicester. A British Academy Conference Grant allowed us to invite to Leicester guest writers Gianni Celati, Daniele Benati, Ermanno Cavazzoni, Jean Talon and Enrico De Vivo, who engaged in lively discussion of their work with the scholars who attended the colloquium. By continuing to work on these and other writers, I came to realise the importance that photography, as well as cinema, art history and aesthetics played in their texts, as in Ghirri’s work. As I furthered my study of Ghirri’s photography and of the context in which he operated, I soon realised that, although the critical literature on his work in Italian is extensive (including the work of Mussini, Quintavalle, Gasparini, Taramelli, D’Elia, Re, Marra), more work was needed to appraise his art in full and from an interdisciplinary angle – the angle that he himself embraced. It also became apparent to me that, despite being widely celebrated in Italy, Ghirri’s art was and still is little known outside of Italy, as not many of his critical essays are available in English translation and few academic publications have appeared in English. Part of the aim of this project is to redress this and to bring Ghirri’s photography to a wider audience, especially outside Italy, and also the to broaden the study of the work of other artists and writers who collaborated with Ghirri or with Celati or who worked independently on urban, rural and marginal or interstitial places, such as, among many, photographers Vittore Fossati and Guido Guidi.

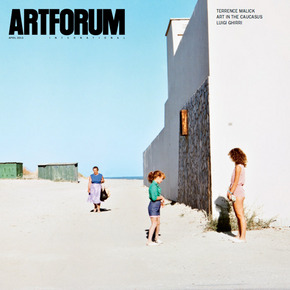

In the last few years Ghirri has increasingly being recognized as one of the leading Italian photographers of the late twentieth-century, both in Italy and abroad, thanks to a greater number of recent publications in English – for example the reprint of his first book, Kodachrome (1978) by MACK (London) in 2013, , and Maria Antonella Pelizzari’s article on Ghirri on Artforum (2013), which gave Ghirri its front cover – and thanks to a growing number of major exhibitions. These include, among others, Elena Re’s Project Prints (Mummery & Schnelle, London, 2011, Castello di Rivoli, Turin, 2012), La Carte d’après nature, curated by Thomas Demand (Nouveau Musée National de Monaco, 2011; Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, 2011) and Kodachrome (Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, 2013). In 2013 Ghirri’s work was exhibited at the Venice Biennale (1 June – 24 November 2013, ), and the MAXXI in Rome organised a major retrospective of his work, curated by Francesca Fabiani, Laura Gasparini and Giuliano Sergio: ‘Luigi Ghirri, ‘Pensare per immagini’’ (23 April-27 October 2013). All these recent exhibitions and works in English testify to the increasing interest in Ghirri’s photography worldwide.

In the last few years Ghirri has increasingly being recognized as one of the leading Italian photographers of the late twentieth-century, both in Italy and abroad, thanks to a greater number of recent publications in English – for example the reprint of his first book, Kodachrome (1978) by MACK (London) in 2013, , and Maria Antonella Pelizzari’s article on Ghirri on Artforum (2013), which gave Ghirri its front cover – and thanks to a growing number of major exhibitions. These include, among others, Elena Re’s Project Prints (Mummery & Schnelle, London, 2011, Castello di Rivoli, Turin, 2012), La Carte d’après nature, curated by Thomas Demand (Nouveau Musée National de Monaco, 2011; Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, 2011) and Kodachrome (Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, 2013). In 2013 Ghirri’s work was exhibited at the Venice Biennale (1 June – 24 November 2013, ), and the MAXXI in Rome organised a major retrospective of his work, curated by Francesca Fabiani, Laura Gasparini and Giuliano Sergio: ‘Luigi Ghirri, ‘Pensare per immagini’’ (23 April-27 October 2013). All these recent exhibitions and works in English testify to the increasing interest in Ghirri’s photography worldwide.

About ten years ago I was introduced to Jacopo Benci by a former graduate student, Kate Litherland, who at the time was carrying out some research at the British School at Rome. Since then Jacopo and I have continued to correspond and exchange ideas about Ghirri and Italian visual arts and cinema. More recently we organised two panels on Luigi Ghirri at the Society for Italian Studies conferences at the University of St. Andrews (July 2011) and of Durham (July 2013). In April 2013 with Jacopo’s support I applied to a British Academy-Leverhulme Small Research Grant in order to continue deepening the study of Luigi Ghirri’s photographic and critical work and, more broadly, to investigate the intersections of Italian photography, literature and space/landscape theory. The award of the British Academy’s funding allowed us to start working on the project in September 2013.

From its onset the project has been well received in Italy, in the UK and elsewhere. The first conference – ‘How to think in images? Luigi Ghirri and photography’, which was held at The British School at Rome on Wednesday 9 October 2013, gathered a wide audience of artists-photographers, scholars and students interested to further the study of Ghirri’s work. A number of people have already joined our network.

William Guerrieri – La fotografia dei ‘luoghi’ e gli autori degli anni Novanta

18 May 2013

The Photography of ‘Places’ and artists of the 1990s

William Guerrieri

Italian photography of the 1980s has been justifiably defined as a photography of ‘places’ despite differences among individual artists. It has been said many times that in photographs of that period the sense of identification with the landscape is expressed through a unified representation of the exterior, alongside the search for beauty, which is considered a defining trait of Italian photography.

However, by the end of the 1980s the development of new infrastructures, urban sprawl, the first waves of immigration and the influence of the media in information and culture meant that in the 1990s a new generation of artists had a different relationship to their environment.

In the work of these artists landscape and urban space are not just represented conventionally through the exterior but also through visual fragments, interior spaces and the re-use of pre-existing images. Nostalgic traits that had sometimes characterized photography of the preceding decade were largely abandoned in favour of a more distanced relationship to the exterior. The use of terms such as ‘hybrid landscape’ and ‘non-place’ introduced the theme of the loss of identity of spaces and the difficulty of organizing a unified representation. One cannot say, however, that the works of these artists adhered to postmodernist strategies since their works continued to maintain a cognitive and ethical approach, which is evidence of their ‘modernity’.

All of the above can be found in the works of some artists from the previous decade, such as Olivo Barbieri and Vincenzo Castella, as well as artists who came to the fore in the early 1990s, such as Paola De Pietri, Paola Di Bello, Marina Ballo Charmet, Francesco Jodice, Walter Niedermayr, Marco Zanta, and myself.

By the end of the 1980s Walter Niedermayr completed a project on the Dolomites, published in 1993 under the title I monti pallidi, which presented groups of photographs arranged both horizontally and vertically. The projects of Paola De Pietri and Marco Zanta ranked among works that revisited urban spaces with a fragmentary and reflexive perspective.

In the context of Italian photography of the 1990s Marina Ballo Charmet set on an original line of activity with an alternative experience of the real through an empathetic relationship to the urban space and the bodies that she explored.

Francesco Jodice’s works on the people living in large urban areas, such as the project Cartoline dagli altri spazi (1998), deal with a ‘sense of non-belonging’ [‘disappartenenza’]. Finally, in my work in Ambienti Pubblici from 1991, I explored the interiors of public spaces of uncertain function and identity. In Identità di Gruppo (1995) I used ‘found’ images for my study on the identitary culture of volunteering.

Although this generational shift has not yet adequately been set in a historical perspective, the linguistic rupture as well as elements of continuity (the use of colour, the relationship between natural and artificial, the perception of the visible) manifesting themselves in the works of these photographers may be glimpsed in publications of the period, such as Forma. Visione e visioni (1994) and Passaggi (1996), some public research projects carried out from the mid-nineties, such as Venezia-Marghera (1997) and Via Emilia. Luoghi e non luoghi (1999 and 2000), and the exhibtion Idea di Metropoli (2002).

These artists were often seen as the ‘inheritors’ of the artists who had preceded them. This may be true from the point of view of training, as various artists of the 1980s were seen as masters in absence of institutional training in photography; it does not, however, apply in terms of the language used and the relationship to the environment, factors that are affected by the influence of international practice (to which the younger artists pay particular attention).

The philosophical and cultural debate of the latest decade, which developed around the need to rebuild an ethical and civil vision through a renewed relationship to the real, thus overcoming postmodernism, brought about a reappraisal and rethinking of 1980s photography of ‘place’.

The reoccurrence of a sentimental relationship to the living environment (often through portraiture) can be found today, for example, in the work of authors such as Francesco Neri, Sabrina Ragucci, Federico Covre, and Cesare Fabbri as well as some photographers of the 1990s. Some other works, referring to the principles of public art, have focused on the identity aspect of place.

Finally, with reference to the research promoted by Linea di Confine (cultural association for contemporary photography based in Rubiera, Reggio Emilia), I have proposed to use the expression ‘coscienza di luogo’ [‘place consciousness/awareness’], where place is the seat of the phenomena and flows ascribable to globalisation. In this perspective the notion of ‘place’ – rather than expressing the return to a nostalgic vision – can take on a new usefulness in investigating the contemporary.

Cesare Ballardini, ‘Dal vero’, 2011

by Jacopo Benci, 10 June 2013

The photography of Cesare Ballardini stands somewhere on a line connecting the photography of Guido Guidi – who portrays anonymous places in a pared down, anti-heroic, melancholic, decentred way, using black and white alongside de-saturated colour – to that of Luigi Ghirri, which by comparison appears maximalistic: axial, symmetrical, pictorial, rich in its colour, and as tied to photography as it is to painting (from Piero della Francesca and Angelico, to de Chirico, Morandi and Magritte). Maybe Ballardini’s work hovers closer to the former than the latter. His artistic history, however, can be placed under the aegis of both practitioners. Born in Fusignano, in the province of Ravenna, in 1954, he studied photography with Italo Zannier, who had also taught Guidi in the 1960s, but his work was first shown in Iconicittà: a vision on the real, an exhibition curated by Ghirri in Ferrara, in 1979.

Valle Santa

Cesare Ballardini, ‘Valle Santa’, 1986

The black and white photographs presented in the book Dal vero (From life) – published in 2011 by Edizioni del Bradipo and edited by Luca Nostri, as part of the project Lugo Land – were chosen in 2009-10 by Ballardini among those he had taken between 1985 and ’89 while he was becoming involved in a cultural association, I Figli del Deserto (The Children of the Desert), founded in Lugo, Romagna, in 1986, of which he was among the first members. The first endeavour of the association was Traversate del deserto (Desert crossings), an exhibition and publication involving – among others – authors Giorgio Agamben, Jean Baudrillard, Gianni Celati, Max Frisch, Gabriel Josipovici, Gilles Lipovetsky, Giuliano Scabia, and photographers Olivo Barbieri, Vittore Fossati, Luigi Ghirri, Guido Guidi.

The book Dal vero contains 22 photographs that Ballardini took in various locations, only a few kilometres apart from each other, in towns and villages such as Lugo, Fusignano, Bagnacavallo, Faenza, Alfonsine. Even in their names these places appear modest, simple, everyday. And the places devoid of human presence in the photographs are just as anonymous: simple cubic houses, a grassy embankment, a well-worn road sign, building materials depots, ploughed fields, reed beds, gas stations, small factories, old cars, deserted suburban roads; during the day, at dusk, at night…

The book Dal vero contains 22 photographs that Ballardini took in various locations, only a few kilometres apart from each other, in towns and villages such as Lugo, Fusignano, Bagnacavallo, Faenza, Alfonsine. Even in their names these places appear modest, simple, everyday. And the places devoid of human presence in the photographs are just as anonymous: simple cubic houses, a grassy embankment, a well-worn road sign, building materials depots, ploughed fields, reed beds, gas stations, small factories, old cars, deserted suburban roads; during the day, at dusk, at night…

Writing about the meaning the word ‘desert’ had for I Figli del Deserto, Celati noted that in the contemporary epoch, “the desert becomes more and more a path to be taken again, a way to be found again, a silence to traverse, in order to be able to still talk with others”. And he added, “the desert is this path: it is the way of silence, the celebration of the small oasis, the discovery of some mythical, gleaming, dazzling, touching trace, the presence of a flower, an animal, a stone, in the indifferent planetary desert – what in any case is called Nature”.

The atmosphere in Ballardini’s photographs is suspended and melancholy, but at the same time he strives not to be too evocative and lyrical. This comes fairly close to the work Guido Guidi was making in the same period, or the images Stephen Shore would take only a few years later, in 1993, at Luzzara, where Zavattini and Paul Strand had made Un paese.

Cesare Ballardini, ‘Villa Pianta’, 1986

A Letter to Guido Guidi, Mohammadreza Mirzaei

by Mohammadreza Mirzaei (translated into English by Oliver Brett), 1 July 2013

Mohammadreza Mirzaei is an Iranian photographer, writer and translator. His recent book What I Don’t Have is published in Italy by Edizioni del Bradipo. He is also the translator of La Grammatica di Dio; short stories by Stefano Benni, from the Italian to the Persian.

Dear Guido,

I hope you are well.

It is more than a year since we last met. I remember it well; it was the day after our conversation at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ravenna when Luca Nostri and I came to your house, that beautiful place in the middle of nowhere called Ronta. We had a discussion and spoke again about Luigi before returning to our previous conversation about landscape. I spoke about Neorealist Cinema and how, at times, landscapes have been foregrounded instead of remaining in the background. I spoke about Visconti’s Ossessione, Antonioni’s Il Grido and Il Deserto Rosso, Zavattini’s and Strand’s Un Paese (and the issue of landscape in these films) and about an Italy without clichés (i.e. the Alps, Florence, Siena, Rome, Umbria, the South, Capri, the islands, the sea…). I also spoke about its humid climate, its white and milky light, and its grey and foggy winters. I asked you if you and Luigi had experienced an image of your land before cinema. I knew that that landscape was yours and that no other photographer had worked there. You were both born and raised there. That landscape was yours, but sometimes I think it is necessary to change it with something else, a metaphor or something similar but greater than Emilia-Romagna or Modena.

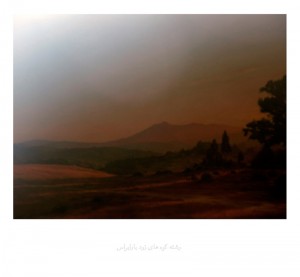

When I spoke of experiencing landscape through an image and not nature (or perhaps where nature finishes), I was honestly thinking about myself. The time spent in Emilia Romagna, discussing Italian photography and ideas such as location, the city, the margins, and, finally, landscape, was so different from my childhood in Tehran. There, I used to see only smog, traffic, crowds of people on the bus or the underground. When I was ten years old I could see the snow-capped Alborz mountains from the balcony of our apartment. It did not take long before the sky scrapers and residential complexes blocked my view. Years later, it was photographs of landscapes that pleased me. They were like a fantasy, something which I could not see in real life. And besides I loved photography, and landscapes were part of its history; even if the fantasy is unreachable, artificial and abstract, like the experiences I had with nature two months ago on the West Coast of the United States.

Robert Adams, in Beauty in Photography, speaks of the autobiographical quality of photographers’ works dealing with landscape. I grew up with photographs, and I have had a strange but also solid and continuous relationship with the land. Being on the West Coast of the United States made me face the challenge of getting close to nature. I was thinking about the concept of the imaginary, of the moment when an apparition occurs out of something which cannot possibly appear. As in yours and Luigi’s photographs and the stories of Dino Buzzati or Italo Calvino, I was looking for that moment. The impossible made possible through my photographic machine, that moment when the light is more bright or dark, that moment when I have discovered the landscape as seen on a postcard or in a shop window display while food shopping. In those moments it was as if I had found a part of me, a fragment of my life in the photograph. Hopefully, I was thinking of the landscape not like that characterized by Adams, with a geographic significance, but as something capable of creating a new geography from a new beginning. It can be like the first and last look.

As a result I am not sure that my photographs are all linked to the West Coast. In those years, while wandering the streets of different countries of the world, I knew that it was not easy for me to establish a personal relationship with any city. It seems that the photographs have something of the place in which I find myself and also something of that city that I cannot mentally leave. It is as if all the photographs had still been taken in Tehran. I would like to share with you some of those photographs and link them into our discussion, even if a year and a few months late. I am still thinking of all the discussions we have shared.

Thank you for everything,

Mohammadreza

The Uncanny Seascapes of Luigi Ghirri

by Nancy Goldring, 22 November 2014

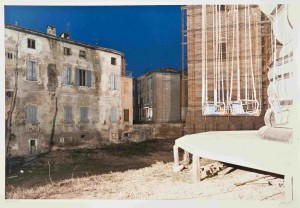

Last year just before leaving Polignano al Mare in Puglia where I had gone to draw, I realized I hadn’t visited the one small museum in town – the Pino Pascali. Among the works in the collection I was surprised to encounter a dark and strange photograph which I immediately recognized as a work of Luigi Ghirri. The photograph revealed a Polignano hidden beneath the bright sunny skies and picturesque village with its quiet cafes. I troubled over what the photograph seemed to reveal about the place. Ghirri had focused on a small cluster of houses, illuminated by a soft light glowing within an impenetrable inky black world.

Here the isolated building is shown cut off from the old town which presides over the sea from a steep cliff. What came immediately to mind as I pondered Ghirri’s take on Polignano was Anthony Vidler’s notion of the uncanny. In his seminal study The Architectural Uncanny, published in 1992. Vidler describes the uncanny as "sinister, disturbing, suspect, strange, fostering dread rather than terror, deriving its force from its very inexplicability, its sense of lurking unease rather from any clearly definite – source of fear – an uncomfortable sense of haunting rather than a present apparition".

He cites Freud’s definition: “beyond ken” – beyond knowledge – from “canny” meaning possessing knowledge rather than skill.

As I studied the photograph, Vidler’s description seemed apt – for while these simple houses in the fishing village might have seemed ordinary – and even familiar, through Ghirri’s eyes they assume an unfamiliarity – almost the way some long-time friend after many years of intimacy, might suddenly reveal a new and disturbing aspect that alters our perception of their character indelibly. We perceive them as both familiar and yet uncomfortably estranged.

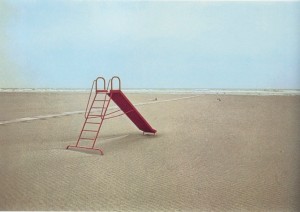

When compared with some of Ghirri’s other photographs of seaside locations, we sense the wide range of his complex approach to image-making. He had a subtle way of detecting and depicting the threshold between the natural landscape and the human presence, often allowing only a tiny remnant from an event or activity to appear in the frame. These triggering elements seem like anti-monuments – for they are human size and without gestures that command attention. Instead, they register a sense of repeated, timeless abandonment.

When compared with some of Ghirri’s other photographs of seaside locations, we sense the wide range of his complex approach to image-making. He had a subtle way of detecting and depicting the threshold between the natural landscape and the human presence, often allowing only a tiny remnant from an event or activity to appear in the frame. These triggering elements seem like anti-monuments – for they are human size and without gestures that command attention. Instead, they register a sense of repeated, timeless abandonment.

In these beach scenes like stage sets left vacant by their actors, we might detect an uncanny of a different sort. The meagre vestiges of the human presence or activity have marked the place, changing it irrevocably. Ghirri accomplishes this transmutation – like the ‘sea change’ suffered in ‘The Tempest’ song with its haunting ring – with a minimum of information. These transforming elements, evidence of human presence, appear to have wandered casually into the viewfinder, yet they provide the clue for understanding the photograph’s meaning. Without them the image would appear to have lost its core – something would seem missing. They provide a small instance of a disquieting human incursion which, when compounded beyond the single example, implies a larger discord in our contemporary world – a cultural uncanny.

This subtly disturbing aspect is reinforced by the color scheme. In these works Ghirri has employed the bright colors of people at play – the reds and yellows of children’s toys. Soon however, the plastic brightness begins to turn sour in the way a clown‘s face elicits delight and then assumes a potentially threatening form – to cite Vidler -we have ‘the sense of the haunting presence rather than the apparition itself’.’

In the Polignano works he deploys a different approach–one that engenders the photographs with a more obvious strain of the uncanny. At glance these appear to be documents – a study of place – a specific place at a specific moment. But it is Ghirri’s selection of the time and place, as well as the framing that produce the sinister feeling emitted by the works. Pipppo Ciorra, in Luigi Ghirri. Pensare per Immagini, offers insights into this process in his discussion of the way Ghirri retreats from the notion of traditional documentation: "Costruisce cioè un documento che è capace di sedimentare senso e di spogliarsi istantaneamente della condizione di documento." […that is, he constructs a document that is capable of generating layers of meaning of instantly stripping it of the condition or notion of documentation.]

Thus the photograph becomes something else – both more and less than a mere recording. Ghirri’s retreat from documentation allows him to destabilize the images permitting other meanings to accrue and infiltrate our reading. In Luigi Ghirri e l’Architettura, Ghirri is quoted as saying: "Ultimately, perhaps, places are simply waiting for someone to look at them, to recognize them. Perhaps these places belong more to our existence than to modernity. They are perhaps waiting for new words or new figures."

That said, we begin to see how the uncanny seeps into the Polignano photos by casting the ordinary and the quotidian in a new light. The late Paola Ghirri writes in an interview in Vintage: ‘non lo interessa mostrare una Puglia troppo bella’ [Luigi wasn’t interested in showing a Puglia that was too beautiful].

The reassurances of the heimlich in this photo offer small comfort. I considered how and why he sought out such a dark vision – why he chose to see the village as suffused with a pervasive gloomy foreboding, almost as if in warning. The photo elicits irresolvable questions rather than providing answers. Where did the people go? Are the lights on as a beacon or merely to create a luminous safe-haven? The woman in profile so carefully framed in the window doesn’t look out into the dark world, but instead she avoids our gaze. What is she doing and what would she see if she directed her vision outwards to peer into the darkness? All of these questions lead to a larger issue: whether the darkness of these photographs in some way records Ghirri’s state of mind or is this instead one of the aspects or qualities he discerned about the place. Or might he have gravitated to places that corresponded to his state of mind? Interestingly, most Ghirri photographs seem free from the personal psychological eye.

Nancy Goldring-Photograph, Polignano, 2012

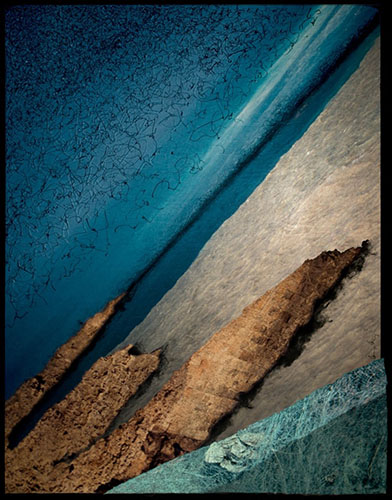

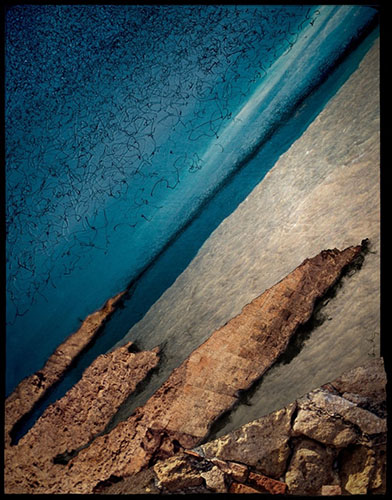

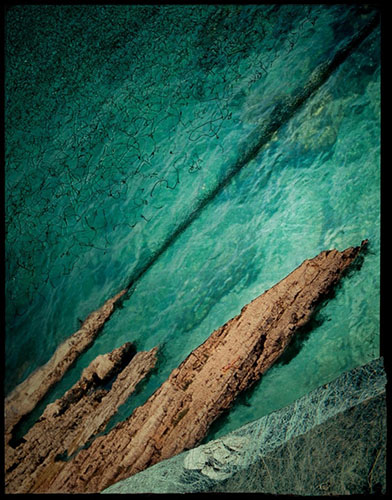

Having detected a powerful strain of the uncanny in Ghirri’s work in Polignano, I began to ponder my own work done there. After a year and a half, I have just finished a series based on my stay there. When I showed the series to an Italian film-maker friend – he made a one word comment: ‘cupo!’ – (dark in the sense of haunting) and then I suddenly saw them in a different way. He found them unsettling and dark just in the way I had responded to the Ghirri images. But to understand how the piece, Sea Saw evolved, I will explain the process by which these images were made. While my work differs technically from that of Ghirri, we share a common conceptual approach.

Like Ghirri, I have a daily practice that structured my days in Polignano – as it does elsewhere – making a drawing a day of the same view. In his series L’infinito (2001)–Ghirri adopted a similar conceptual practice – shooting the clouds daily for a year. In this way his time frame seems to circumscribe the infinite space of the sky. Ghirri wasn’t impelled by the notion of nature photography and the impulse behind the work wasn’t the exquisite spectacle of those clouds scooting across the azure sky. He says in L’infinito: "Non ho mai amato le fotografie della “natura”. Da quelle in cui la natura appare nei suoi aspetti misteriosi o metafisici, alle forzature astratte dei segni o pamiture di colore. Ho sempre trovato in queste immagini, e nel disperato tentative di bloccare il “momento naturale” una contraddizione insanabile con il linguaggio fotografico." [I have never loved nature photography, those photos in which nature appears in its mysterious and metaphysical aspect or those where signs and colors are forced into an abstract language. I have always thought that such images in their desperate attempt to fix the “natural moment” slip into a state of unhealthy contradiction with the language of photography.]

If we are to trust his statement we must therefore understand the series as an essentially conceptual project with a theme involving a sense of transience and the ineffable. The series registers the act of looking over 365 days – finding sameness and distinguishing difference. Perhaps in a similar way, the core of my project has at its core a conceptual basis in that the viewer is invited to read the sequence of images that I constructed from perceptual information, and to begin to detect the shifts and changes among them

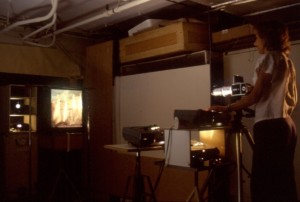

Connected with this conceptual component is the freedom with which we both use the medium of photography. In some of his early work he experimented with mixed media combining graphic and photographic means and melding them into a single image. He and artist Franco Guerzoni produced collaborative work whose structure and meaning were cemented purely through a conceptual reading. In my explorations I have also blurred the lines among traditional media to produce a delicately hinged hybrid form – graphic, photographic, and projected with a sense that all three are required for producing the image.

Connected with this conceptual component is the freedom with which we both use the medium of photography. In some of his early work he experimented with mixed media combining graphic and photographic means and melding them into a single image. He and artist Franco Guerzoni produced collaborative work whose structure and meaning were cemented purely through a conceptual reading. In my explorations I have also blurred the lines among traditional media to produce a delicately hinged hybrid form – graphic, photographic, and projected with a sense that all three are required for producing the image.

The summer of 2013 I spent some 3 weeks perched high over the sea in a tiny, humid house carved directly from the cliff in Polignano al Mare. The balcony where I spent some seven hours a day drawing, afforded more than a 180 degree view of the sea, a few sparse buildings and rocky shore. I drew with the morning light and in the late afternoon contraluce that plunged the shore into murky shadow. As I photographed the sky and water continuously, I began to extract a sense of this place – how it was unlike any other and what lay beneath its evident surface qualities.

Frustrated by the limitations of my smallish drawing pad I reoriented the drawing to allow the horizon to reach diagonally across the page. What resulted then was an unbalancing of the composition so that vantage point would have no spot to hold onto, it glided along the horizon with no purchase on a secure viewpoint – thereby rendering the sea a potentially dangerous presence. In an interview in the catalogue for Vintage (2008, Editrice Quinlan), curated by Berardo Celati, the late Paola Ghirri describes a similar response to the sea in Puglia: "…e il mare era un elemento che forse gli faceva paura e puo essere che abbia sentito il bisogno di tenerlo a una debita distanza mettendo sempre qualcosa tra se e quel orrizonte blu ed assoluto." […and the sea was an element that frightened him, perhaps there was a need to keep it at a calculated distance always putting something between himself and the absoluteness of that blue horizon.]. Thus, from its initial impulse, the central construct of sea and sky that evolved from my early sketches establish a precarious and disturbing foundation.’

Wallace Stevens came to mind: In Sea Surface full of Clouds (1931) he writes:

"…And a sham-like green

Capped summer-seeming on the tense machine

Of ocean, which in sinister flatness lay.

Who, then, beheld the rising of the clouds

That strode submerged in that malevolent sheen,"

Once back in my NY studio I began to embroider the original drawing –and contrived a low relief collage onto which to project bits and pieces of the slides I had taken. This collage served as an architecture for the piece. Photographing the superimpositions (the slides onto the relief), I developed a non-narrative series of images – perhaps twenty-five – of which I have printed only seven. Together they suggest the intricate nature of human perception by re-ordering visual information to propose irreconcilable time frames, shifting vantage points, changing moods, and memory traces. Together they reflect the complex way we experience the world. What brings my approach close to that of Ghirri’s is the way these images suggest various modes of looking – contemplation, rumination, and reverie – but a mode that refuses to reassure.

In some of the images I have taken bits and pieces of the architecture of the town and confounded them with the natural setting – to conjure the way we carry memory images when they have been unleashed from geography or locus. In others I have recomposed the composition to see the dizzying view from the balcony directly into the water beneath. The piece attempts to fathom the way the sky – with its infinite depth – enfolds us in breathable air and atmosphere and touches the ever-elusive horizon that tries to mark the edge of the sea extending towards slicing the world in planer fashion as it too recedes into immeasurable space. Just as Ghirri tamed his empty spaces framing them like thoughts, the elements of my view provided a structure or base for the facts of the place. They are all ‘true’ – as in Ghirri’s photos – even if contradictory and ambiguous – and it is precisely that ambiguity that calls to mind the uncanny.

Again to quote Vidler: "As a concept, then, the uncanny has, not unnaturally, found its metaphorical home in architecture: first, in the house haunted or not, that pretends to afford the utmost security while opening itself to the secret intrusion of terror…… of course the uncanny is not a property of the space itself nor can it be provoked by any particular spatial conformation; it is, in its aesthetic dimension, a representation of a mental state of projection that precisely elides the boundaries of the real and the unreal in order to provoke a disturbing ambiguity, a slippage between waking and dreaming…the architectural uncanny is necessarily ambiguous, combining aspects of its fictional history, its psychological analysis and its cultural manifestations. If actual buildings or spaces are interpreted through this lens it is not because they themselves possess uncanny properties, but rather because they act, historically or culturally as emblems of estrangement.