Richard III: Discovery and identification

Richard III's diet and lifestyle

Analysis of the king’s skeleton not only aided its identification but also provided new insights into Richard III’s diet and lifestyle.

You are what you eat

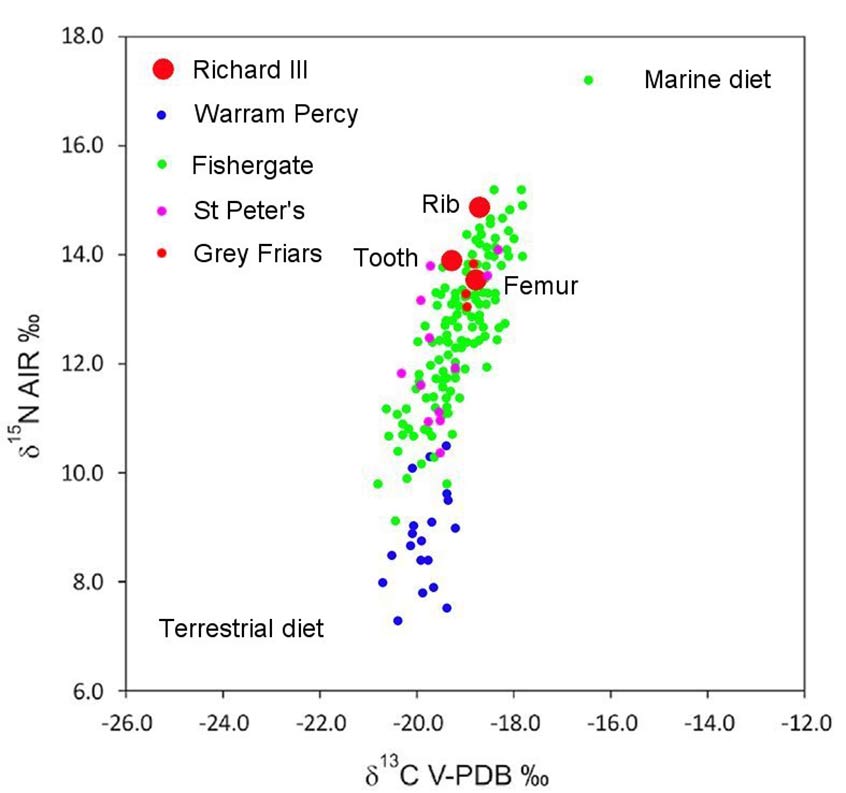

Bone contains many chemical elements including carbon (C), nitrogen (N), oxygen (O) and strontium (Sr). These exist in different forms, known as isotopes. By measuring these isotopes (13C/12C and 15N/14N, 18O, 87Sr/86Sr) preserved in Richard III’s teeth and bone collagen, we can find out about the types of food and drink he consumed, as well as where he lived. Importantly, different parts of the skeleton can provide information about particular stages of a person’s life. Samples were taken from the king’s teeth (which formed during his childhood and early adolescence), a femur (which averages his adulthood) and a rib (which represents the last few years of his life) allowed the king’s life history to be examined.

The isotope values of oxygen and strontium in bone can be linked to the geologic (strontium) and climatic (oxygen) environment in which a person lived; strontium isotope composition provides links to the land where food was grown or grazed, and oxygen is linked to the source of drinking water. Results suggested that Richard moved out of eastern England, where he was born, by the age of seven or eight, residing further west; but moved back into eastern England as an adolescent or young adult. Whilst this data did not provide a tightly constrained location it was consistent with historically documented geographical movements during Richard III’s childhood. He was born in 1452 and spent his very early childhood at Fotheringhay in Northamptonshire before moving to Ludlow Castle in the Welsh Marches for a period in 1459.

Data also showed that Richard had a mixed, protein-rich diet. Carbon and nitrogen in the bone tell us about the source of protein that was eaten – whether it came predominately from plants or animals, and whether it was mainly terrestrial (land) or marine based (fish). The terrestrial element from Richard’s diet was mostly from meat, whilst perhaps a quarter was derived from seafood. A varied diet of this kind would have been typical of a late medieval nobleman, who could afford to consume expensive foods like meat, game and fish. Differences in the values obtained from his femur and rib bone also suggested an increase in feasting and in the consumption of imported wine in the last few years of Richard’s life. Kingship had evidently brought about a significant change in lifestyle.

More information on Richard III’s diet and lifestyle is freely available online in this peer-reviewed academic paper, Multi-isotope analysis demonstrates significant lifestyle changes in King Richard III.

Stomach troubles

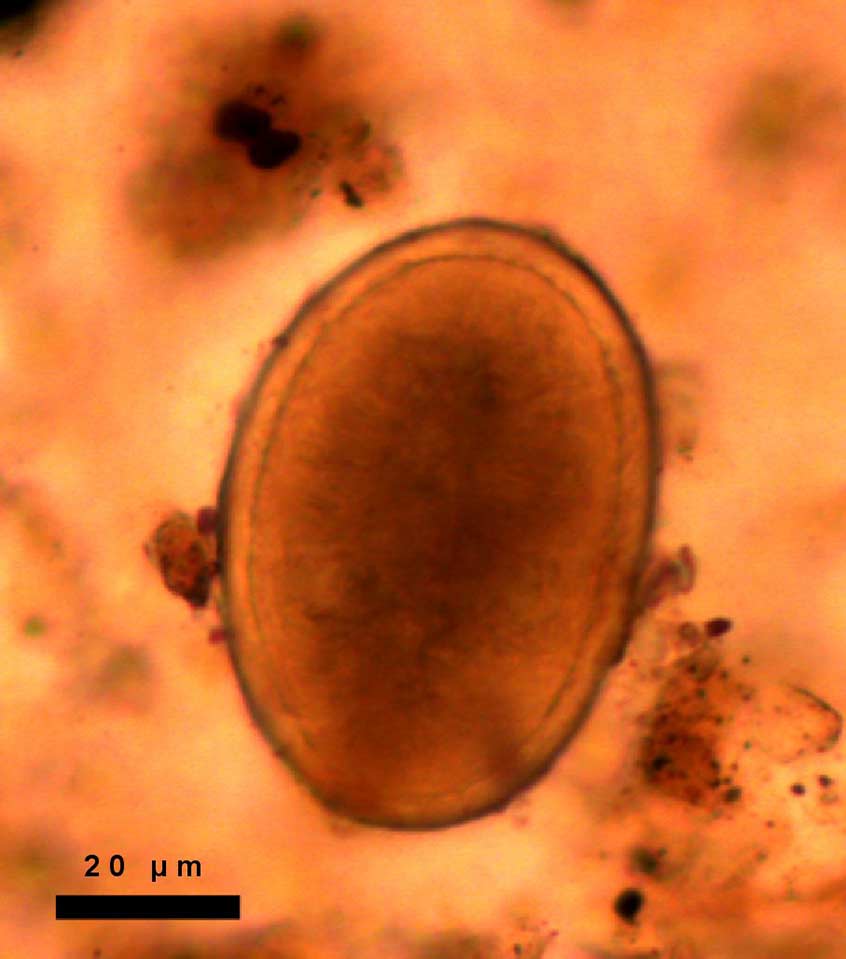

As part of the investigation of his diet and health, soil samples were taken from within the gut area of Richard III’s skeleton and analysed to see if they contained any evidence for food residues (such as pollen grains, seeds or fragments of plant tissue) or intestinal parasites.

The presence of microscopic egg casings showed that Richard III was infected with roundworm, an intestinal parasite which uses the human body as a host in order to survive and reproduce. The infection is normally transmitted via human faecal matter as a result of poor personal hygiene, either from consuming contaminated food or water or from making contact with soil where human waste has been used as fertilizer. Such conditions were of course common in the medieval period.

In high-status medieval households, there were well-established rituals of handwashing so it is perhaps most likely that Richard III caught the infection from food prepared by servants who were rather less fastidious in their personal habits. We cannot be sure of the level of infection – minor cases might have little effect on health, although severe cases can lead to acute bowel problems, malnutrition and stunted growth. Many people in medieval England would have carried this parasite. There was no evidence of other intestinal parasites such as tapeworm, which is transmitted by the consumption of infected meat; this suggests that Richard III’s food was being cooked thoroughly.

More information on Richard III’s stomach troubles is freely available online in this peer-reviewed academic paper, The intestinal parasites of King Richard III.